by The Invisible Committee

Translated from the French, 2007

From whatever angle you approach it, the present offers no way out. This is not the least of its virtues. From those who seek hope above all, it tears away every firm ground. Those who claim to have solutions are contradicted almost immediately. Everyone agrees that things can only get worse. “The future has no future” is the wisdom of an age that, for all its appearance of perfect normalcy, has reached the level of consciousness of the first punks.

The sphere of political representation has come to a close. From left to right, it’s the same nothingness striking the pose of an emperor or a savior, the same sales assistants adjusting their discourse according to the findings of the latest surveys. Those who still vote seem to have no other intention than to desecrate the ballot box by voting as a pure act of protest. We’re beginning to suspect that it’s only against voting itself that people continue to vote. Nothing we’re being shown is adequate to the situation, not by far. In its very silence, the populace seems infinitely more mature than all these puppets bickering amongst themselves about how to govern it. The ramblings of any Belleville chibani contain more wisdom than all the declarations of our so-called leaders. The lid on the social kettle is shut triple-tight, and the pressure inside continues to build. From out of Argentina, the specter of Que Se Vayan Todos is beginning to seriously haunt the ruling class.

The flames of November 2005 still flicker in everyone’s minds. Those first joyous fires were the baptism of a decade full of promise. The media fable of “banlieue vs. the Republic” may work, but what it gains in effectiveness it loses in truth. Fires were lit in the city centers, but this news was methodically suppressed. Whole streets in Barcelona burned in solidarity, but no one knew about it apart from the people living there. And it’s not even true that the country has stopped burning. Many different profiles can be found among the arrested, with little that unites them besides a hatred for existing society – not class, race, or even neighborhood. What was new wasn’t the “banlieue revolt,” since that was already going on in the 80s, but the break with its established forms. These assailants no longer listen to anybody, neither to their Big Brothers and Big Sisters, nor to the community organizations charged with overseeing the return to normal. No “SOS Racism” could sink its cancerous roots into this event, whose apparent conclusion can be credited only to fatigue, falsification and the media omertà. This whole series of nocturnal vandalisms and anonymous attacks, this wordless destruction, has widened the breach between politics and the political. No one can honestly deny the obvious: this was an assault that made no demands, a threat without a message, and it had nothing to do with “politics.” One would have to be oblivious to the autonomous youth movements of the last 30 years not to see the purely political character of this resolute negation of politics. Like lost children we trashed the prized trinkets of a society that deserves no more respect than the monuments of Paris at the end of the Bloody Week- and knows it.

There will be no social solution to the present situation. First, because the vague aggregate of social milieus, institutions, and individualized bubbles that is called, with a touch of antiphrasis, “society,” has no consistency. Second, because there’s no longer any language for common experience. And we cannot share wealth if we do not share a language. It took half a century of struggle around the Enlightenment to make the French Revolution possible, and a century of struggle around work to give birth to the fearsome “welfare state.” Struggles create the language in which a new order expresses itself. But there is nothing like that today. Europe is now a continent gone broke that shops secretly at discount stores and has to fly budget airlines if it wants to travel at all. No “problems” framed in social terms admit of a solution. The questions of “pensions,” of “job security,” of “young people” and their “violence” can only be held in suspense while the situation these words serve to cover up is continually policed for signs of further unrest. Nothing can make it an attractive prospect to wipe the asses of pensioners for minimum wage. Those who have found less humiliation and more advantage in a life of crime than in sweeping floors will not turn in their weapons, and prison won’t teach them to love society. Cuts to their monthly pensions will undermine the desperate pleasure-seeking of hordes of retirees, making them stew and splutter about the refusal to work among an ever larger section of youth. And finally, no guaranteed income granted the day after a quasi-uprising will be able to lay the foundation of a new New Deal, a new pact, a new peace. The social feeling has already evaporated too much for that.

As an attempted solution, the pressure to ensure that nothing happens, together with police surveillance of the territory, will only intensify. The unmanned drone that flew over Seine-Saint-Denis last July 14th – as the police later confirmed – presents a much more vivid image of the future than all the fuzzy humanistic projections. That they were careful to assure us that the drone was unarmed gives us a clear indication of the road we’re headed down. The territory will be partitioned into ever more restricted zones. Highways built around the borders of “problem neighborhoods” already form invisible walls closing off those areas off from the middle-class subdivisions. Whatever defenders of the Republic may think, the control of neighborhoods “by the community” is manifestly the most effective means available. The purely metropolitan sections of the country, the main city centers, will go about their opulent lives in an ever more crafty, ever more sophisticated, ever more shimmering deconstruction. They will illuminate the whole planet with their glaring neon lights, as the patrols of the BAC and private security companies (i.e. paramilitary units) proliferate under the umbrella of an increasingly shameless judicial protection.

The impasse of the present, everywhere in evidence, is everywhere denied. There will be no end of psychologists, sociologists, and literary hacks applying themselves to the case, each with a specialized jargon from which the conclusions are especially absent. It’s enough to listen to the songs of the times – the asinine “alt-folk” where the petty bourgeoisie dissects the state of its soul, next to declarations of war from Mafia K’1 Fry – to know that a certain coexistence will end soon, that a decision is near.

This book is signed in the name of an imaginary collective. Its editors are not its authors. They were content merely to introduce a little order into the common-places of our time, collecting some of the murmurings around barroom tables and behind closed bedroom doors. They’ve done nothing more than lay down a few necessary truths, whose universal repression fills psychiatric hospitals with patients, and eyes with pain. They’ve made themselves scribes of the situation. It’s the privileged feature of radical circumstances that a rigorous application of logic leads to revolution. It’s enough just to say what is before our eyes and not to shrink from the conclusions.

First Circle

“I AM WHAT I AM”

“I AM WHAT I AM.” This is marketing’s latest offering to the world, the final stage in the development of advertising, far beyond all the exhortations to be different, to be oneself and drink Pepsi. Decades of concepts in order to get where we are, to arrive at pure tautology. I = I. He’s running on a treadmill in front of the mirror in his gym. She’s coming back from work, behind the wheel of her Smart car. Will they meet?

“I AM WHAT I AM.” My body belongs to me. I am me, you are you, and something’s wrong. Mass personalization. Individualization of all conditions – life, work and misery. Diffuse schizophrenia. Rampant depression. Atomization into fine paranoiac particles. Hysterization of contact. The more I want to be me, the more I feel an emptiness. The more I express myself, the more I am drained. The more I run after myself, the more tired I get. We cling to our self like a coveted job title. We’ve become our own representatives in a strange commerce, guarantors of a personalization that feels, in the end, a lot more like an amputation. We insure our selves to the point of bankruptcy, with a more or less disguised clumsiness.

Meanwhile, I manage. The quest for a self, my blog, my apartment, the latest fashionable crap, relationship dramas, who’s fucking who… whatever prosthesis it takes to hold onto an “I”! If “society” hadn’t become such a definitive abstraction, then it would denote all the existential crutches that allow me to keep dragging on, the ensemble of dependencies I’ve contracted as the price of my identity. The handicapped person is the model citizen of tomorrow. It’s not without foresight that the associations exploiting them today demand that they be granted a “subsistence income.”

The injunction, everywhere, to “be someone” maintains the pathological state that makes this society necessary. The injunction to be strong produces the very weakness by which it maintains itself, so that everything seems to take on a therapeutic character, even working, even love. All those “how’s it goings?” that we exchange give the impression of a society composed of patients taking each other’s temperatures. Sociability is now made up of a thousand little niches, a thousand little refuges where you can take shelter. Where it’s always better than the bitter cold outside. Where everything’s false, since it’s all just a pretext for getting warmed up. Where nothing can happen since we’re all too busy shivering silently together. Soon this society will only be held together by the mere tension of all the social atoms straining towards an illusory cure. It’s a power plant that runs its turbines on a gigantic reservoir of unwept tears, always on the verge of spilling over.

“I AM WHAT I AM.” Never has domination found such an innocent-sounding slogan. The maintenance of the self in a permanent state of deterioration, in a chronic state of near-collapse, is the best-kept secret of the present order of things. The weak, depressed, self-critical, virtual self is essentially that endlessly adaptable subject required by the ceaseless innovation of production, the accelerated obsolescence of technologies, the constant overturning of social norms, and generalized flexibility. It is at the same time the most voracious consumer and, paradoxically, the most productive self, the one that will most eagerly and energetically throw itself into the slightest project, only to return later to its original larval state.

“WHAT AM I,” then? Since childhood, I’ve passed through a flow of milk, smells, stories, sounds, emotions, nursery rhymes, substances, gestures, ideas, impressions, gazes, songs, and foods. What am I? Tied in every way to places, sufferings, ancestors, friends, loves, events, languages, memories, to all kinds of things that obviously are not me. Everything that attaches me to the world, all the links that constitute me, all the forces that compose me don’t form an identity, a thing displayable on cue, but a singular, shared, living existence, from which emerges – at certain times and places – that being which says “I.” Our feeling of inconsistency is simply the consequence of this foolish belief in the permanence of the self and of the little care we give to what makes us what we are.

It’s dizzying to see Reebok’s “I AM WHAT I AM” enthroned atop a Shanghai skyscraper. The West everywhere rolls out its favorite Trojan horse: the exasperating antimony between the self and the world, the individual and the group, between attachment and freedom. Freedom isn’t the act of shedding our attachments, but the practical capacity to work on them, to move around in their space, to form or dissolve them. The family only exists as a family, that is, as a hell, for those who’ve quit trying to alter its debilitating mechanisms, or don’t know how to. The freedom to uproot oneself has always been a phantasmic freedom. We can’t rid ourselves of what binds us without at the same time losing the very thing to which our forces would be applied.

“I AM WHAT I AM,” then, is not simply a lie, a simple advertising campaign, but a military campaign, a war cry directed against everything that exists between beings, against everything that circulates indistinctly, everything that invisibly links them, everything that prevents complete desolation, against everything that makes us exist, and ensures that the whole world doesn’t everywhere have the look and feel of a highway, an amusement park or a new town: pure boredom, passionless but well-ordered, empty, frozen space, where nothing moves apart from registered bodies, molecular automobiles, and ideal commodities.

France wouldn’t be the land of anxiety pills that it’s become, the paradise of anti-depressants, the Mecca of neurosis, if it weren’t also the European champion of hourly productivity. Sickness, fatigue, depression, can be seen as the individual symptoms of what needs to be cured. They contribute to the maintenance of the existing order, to my docile adjustment to idiotic norms, and to the modernization of my crutches. They specify the selection of my opportune, compliant, and productive tendencies, as well as those that must be gently discarded. “It’s never too late to change, you know.” But taken as facts, my failings can also lead to the dismantling of the hypothesis of the self. They then become acts of resistance in the current war. They become a rebellion and a force against everything that conspires to normalize us, to amputate us. The self is not some thing within us that is in a state of crisis; it is the form they mean to stamp upon us. They want to make our self something sharply defined, separate, assessable in terms of qualities, controllable, when in fact we are creatures among creatures, singularities among similars, living flesh weaving the flesh of the world. Contrary to what has been repeated to us since childhood, intelligence doesn’t mean knowing how to adapt – or if that is a kind of intelligence, it’s the intelligence of slaves. Our inadaptability, our fatigue, are only problems from the standpoint of what aims to subjugate us. They indicate rather a departure point, a meeting point, for new complicities. They reveal a landscape more damaged, but infinitely more sharable than all the fantasy lands this society maintains for its purposes.

We are not depressed; we’re on strike. For those who refuse to manage themselves, “depression” is not a state but a passage, a bowing out, a sidestep towards a political disaffiliation. From then on medication and the police are the only possible forms of conciliation. This is why the present society doesn’t hesitate to impose Ritalin on its over-active children, or to strap people into life-long dependence on pharmaceuticals, and why it claims to be able to detect “behavioral disorders” at age three. Because everywhere the hypothesis of the self is beginning to crack.

Second Circle

“Entertainment is a vital need”

A government that declares a state of emergency against fifteen-year-old kids. A country that takes refuge in the arms of a football team. A cop in a hospital bed, complaining about being the victim of “violence.” A city councilwoman issuing a decree against the building of tree houses. Two ten year olds, in Chelles, charged with burning down a video game arcade. This era excels in a certain situation of the grotesque that seems to escape it every time. The truth is that the plaintive, indignant tones of the news media are unable to stifle the burst of laughter that welcomes these headlines.

A burst of laughter is the only appropriate response to all the serious “questions” posed by news analysts. To take the most banal: there is no “immigration question.” Who still grows up where they were born? Who lives where they grew up? Who works where they live? Who lives where their ancestors did? And to whom do the children of this era belong, to television or their parents? The truth is that we have been completely torn from any belonging, we are no longer from anywhere, and the result, in addition to a new disposition to tourism, is an undeniable suffering. Our history is one of colonizations, of migrations, of wars, of exiles, of the destruction of all roots. It’s the story of everything that has made us foreigners in this world, guests in our own family. We have been expropriated from our own language by education, from our songs by reality TV contests, from our flesh by mass pornography, from our city by the police, and from our friends by wage-labor. To this we should add, in France, the ferocious and secular work of individualization by the power of the state, that classifies, compares, disciplines and separates its subjects starting from a very young age, that instinctively grinds down any solidarities that escape it until nothing remains except citizenship – a pure, phantasmic sense of belonging to the Republic. The Frenchman, more than anyone else, is the embodiment of the dispossessed, the destitute. His hatred of foreigners is based on his hatred of himself as a foreigner. The mixture of jealousy and fear he feels toward the “cités“ expresses nothing but his resentment for all he has lost. He can’t help envying these so-called “problem” neighborhoods where there still persists a bit of communal life, a few links between beings, some solidarities not controlled by the state, an informal economy, an organization that is not yet detached from those who organize. We have arrived at a point of privation where the only way to feel French is to curse the immigrants and those who are more visibly foreign. In this country, the immigrants assume a curious position of sovereignty: if they weren’t here, the French might stop existing.

France is a product of its schools, and not the inverse. We live in an excessively scholastic country, where one remembers passing an exam as a sort of life passage. Where retired people still tell you about their failure, forty years earlier, in such and such an exam, and how it screwed up their whole career, their whole life. For a century and a half, the national school system has been producing a type of state subjectivity that stands out amongst all others. People who accept competition on the condition that the playing field is level. Who expect in life that each person be rewarded as in a contest, according to their merit. Who always ask permission before taking. Who silently respect culture, the rules, and those with the best grades. Even their attachment to their great, critical intellectuals and their rejection of capitalism are branded by this love of school. It’s this construction of subjectivities by the state that is breaking down, every day a little more, with the decline of the scholarly institutions. The reappearance, over the past twenty years, of a school and a culture of the street, in competition with the school of the republic and its cardboard culture, is the most profound trauma that French universalism is presently undergoing. On this point, the extreme right is already reconciled with the most virulent left. However, the name Jules Ferry – Minister of Thiers during the crushing of the Commune and theoretician of colonization – should itself be enough to render this institution suspect.

When we see teachers from some “citizens’ vigilance committee” come on the evening news to whine about someone burning down their school, we remember how many times, as children, we dreamed of doing exactly this. When we hear a leftist intellectual blabbering about the barbarism of groups of kids harassing passersby in the street, shoplifting, burning cars, and playing cat and mouse with riot police, we remember what they said about the greasers in the 50s or, better, the apaches in the “Belle Époque”: “The generic name apaches,” writes a judge at the Seine tribunal in 1907, “has for the past few years been a way of designating all dangerous individuals, enemies of society, without nation or family, deserters of all duties, ready for the most audacious confrontations, and for any sort of attack on persons and properties.” These gangs who flee work, who adopt the names of their neighborhoods, and confront the police are the nightmare of the good, individualized French citizen: they embody everything he has renounced, all the possible joy he will never experience. There is something impertinent about existing in a country where a child singing as she pleases is inevitably silenced with a “stop, you’re going to stir things up,” where scholastic castration unleashes floods of policed employees. The aura that persists around Mesrine has less to do with his uprightness and his audacity than with the fact that he took it upon himself to enact vengeance on what we should all avenge. Or rather, of what we should avenge directly, when instead we continue to hesitate and defer endlessly. Because there is no doubt that in a thousand imperceptible and undercover ways, in all sorts of slanderous remarks, in every spiteful little expression and venomous politeness, the Frenchman continues to avenge, permanently and against everyone, the fact that he’s resigned himself to being trampled over. It was about time that fuck the police! replaced yes sir, officer! In this sense, the un-nuanced hostility of certain gangs only expresses, in a slightly less muffled way, the poisonous atmosphere, the rotten spirit, the desire for a salvational destruction in which the country is completely consumed.

To call this population of strangers in the midst of which we live “society” is such an usurpation that even sociologists dream of renouncing a concept that was, for a century, their bread and butter. Now they prefer the metaphor of a network to describe the connection of cybernetic solitudes, the intermeshing of weak interactions under names like “colleague,” “contact,” “buddy,” “acquaintance,” or “date.” Such networks sometimes condense into a milieu, where nothing is shared but codes, and where nothing is played out except the incessant recomposition of identity.

It would be a waste of time to detail all that which is agonizing in existing social relations. They say the family is coming back, that the couple is coming back. But the family that’s coming back is not the same one that went away. Its return is nothing but a deepening of the reigning separation that it serves to mask, becoming what it is through this masquerade. Everyone can testify to the rations of sadness condensed from year to year in family gatherings, the forced smiles, the awkwardness of seeing everyone pretending in vain, the feeling that a corpse is lying there on the table, and everyone acting as though it were nothing. From flirtation to divorce, from cohabitation to stepfamilies, everyone feels the inanity of the sad family nucleus, but most seem to believe that it would be sadder still to renounce it. The family is no longer so much the suffocation of maternal control or the patriarchy of beatings as it is this infantile abandon to a fuzzy dependency, where everything is familiar, this carefree moment in the face of a world that nobody can deny is breaking down, a world where “becoming self-sufficient” is a euphemism for “having found a boss.” They want to use the “familiarity” of the biological family as an excuse to eat away at anything that burns passionately within us and, under the pretext that they raised us, make us renounce the possibility of growing up, as well as everything that is serious in childhood. It is necessary to preserve oneself from such corrosion.

The couple is like the final stage of the great social debacle. It’s the oasis in the middle of the human desert. Under the auspices of “intimacy,” we come to it looking for everything that has so obviously deserted contemporary social relations: warmth, simplicity, truth, a life without theater or spectator. But once the romantic high has passed, “intimacy” strips itself bare: it is itself a social invention, it speaks the language of glamour magazines and psychology; like everything else, it is bolstered with so many strategies to the point of nausea. There is no more truth here than elsewhere; here too lies and the laws of estrangement dominate. And when, by good fortune, one discovers this truth, it demands a sharing that belies the very form of the couple. What allows beings to love each other is also what makes them lovable, and ruins the utopia of autism-for-two.

In reality, the decomposition of all social forms is a blessing. It is for us the ideal condition for a wild, massive experimentation with new arrangements, new fidelities. The famous “parental resignation” has imposed on us a confrontation with the world that demands a precocious lucidity, and foreshadows lovely revolts to come. In the death of the couple, we see the birth of troubling forms of collective affectivity, now that sex is all used up and masculinity and femininity parade around in such moth-eaten clothes, now that three decades of non-stop pornographic innovation have exhausted all the allure of transgression and liberation. We count on making that which is unconditional in relationships the armor of a political solidarity as impenetrable to state interference as a gypsy camp. There is no reason that the interminable subsidies that numerous relatives are compelled to offload onto their proletarianized progeny can’t become a form of patronage in favor of social subversion. “Becoming autonomous,” could just as easily mean learning to fight in the street, to occupy empty houses, to cease working, to love each other madly, and to shoplift.

Third Circle

“Life, health and love are precarious – why should work be an exception?”

No question is more confused, in France, than the question of work. No relation is more disfigured than the one between the French and work. Go to Andalusia, to Algeria, to Naples. They despise work, profoundly. Go to Germany, to the United States, to Japan. They revere work. Things are changing, it’s true. There are plenty of otaku in Japan, frohe Arbeitslose in Germany and workaholics in Andalusia. But for the time being these are only curiosities. In France, we get down on all fours to climb the ladders of hierarchy, but privately flatter ourselves that we don’t really give a shit. We stay at work until ten o’clock in the evening when we’re swamped, but we’ve never had any scruples about stealing office supplies here and there, or carting off the inventory in order to resell it later. We hate bosses, but we want to be employed at any cost. To have a job is an honor, yet working is a sign of servility. In short: the perfect clinical illustration of hysteria. We love while hating, we hate while loving. And we all know the stupor and confusion that strike the hysteric when he loses his victim – his master. Most of the time he never recovers.

This neurosis is the foundation upon which successive governments could declare war on joblessness, pretending to wage a “battle on unemployment” while ex-managers camped with their cell phones in Red Cross shelters along the banks of the Seine. While the Department of Labor was massively manipulating its statistics in order to bring unemployment numbers below two million. While welfare checks and drug dealing were the only guarantees, as the French state has recognized, against the possibility of social unrest at each and every moment. It’s the psychic economy of the French as much as the political stability of the country that is at stake in the maintenance of the workerist fiction.

Excuse us if we don’t give a fuck.

We belong to a generation that lives very well in this fiction. That has never counted on either a pension or the right to work, let alone rights at work. That isn’t even “precarious,” as the most advanced factions of the militant left like to theorize, because to be precarious is still to define oneself in relation to the sphere of work, that is, to its decomposition. We accept the necessity of finding money, by whatever means, because it is currently impossible to do without it, but we reject the necessity of working. Besides, we don’t work anymore: we do our time. Business is not a place where we exist, it’s a place we pass through. We aren’t cynical, we are just reluctant to be deceived. All these discourses on motivation, quality and personal investment pass us by, to the great dismay of human resources managers. They say we are disappointed by business, that it failed to honor our parents’ loyalty, that it let them go too quickly. They are lying. To be disappointed, one must have hoped for something. And we have never hoped for anything from business: we see it for what it is and for what it has always been, a fool’s game of varying degrees of comfort. On behalf of our parents, our only regret is that they fell into the trap, at least the ones who believed.

The sentimental confusion that surrounds the question of work can be explained thus: the notion of work has always included two contradictory dimensions: a dimension of exploitation and a dimension of participation. Exploitation of individual and collective labor power through the private or social appropriation of surplus value; participation in a common effort through the relations linking those who cooperate at the heart of the universe of production. These two dimensions are perversely confused in the notion of work, which explains workers’ indifference, at the end of the day, to both Marxist rhetoric – which denies the dimension of participation – and managerial rhetoric – which denies the dimension of exploitation. Hence the ambivalence of the relation of work, which is shameful insofar as it makes us strangers to what we are doing, and – at the same time – adored, insofar as a part of ourselves is brought into play. The disaster has already occurred: it resides in everything that had to be destroyed, in all those who had to be uprooted, in order for work to end up as the only way of existing. The horror of work is less in the work itself than in the methodical ravaging, for centuries, of all that isn’t work: the familiarities of one’s neighborhood and trade, of one’s village, of struggle, of kinship, our attachment to places, to beings, to the seasons, to ways of doing and speaking.

Here lies the present paradox: work has totally triumphed over all other ways of existing, at the very moment when workers have become superfluous. Gains in productivity, outsourcing, mechanization, automated and digital production have so progressed that they have almost reduced to zero the quantity of living labor necessary in the manufacture of any product. We are living the paradox of a society of workers without work, where entertainment, consumption and leisure only underscore the lack from which they are supposed to distract us. The mine in Carmaux, famous for a century of violent strikes, has now been reconverted into Cape Discovery. It’s an entertainment “multiplex” for skateboarding and biking, distinguished by a “Mining Museum” in which methane blasts are simulated for vacationers.

In corporations, work is divided in an increasingly visible way into highly skilled positions of research, conception, control, coordination and communication which deploy all the knowledge necessary for the new, cybernetic production process, and unskilled positions for the maintenance and surveillance of this process. The first are few in number, very well paid and thus so coveted that the minority who occupy these positions will do anything to avoid losing them. They and their work are effectively bound in one anguished embrace. Managers, scientists, lobbyists, researchers, programmers, developers, consultants and engineers, literally never stop working. Even their sex lives serve to augment productivity. A Human Resources philosopher writes,

“[t]he most creative businesses are the ones with the greatest number of intimate relations.” “Business associates,” a Daimler-Benz Human Resources Manager confirms, “are an important part of the business’s capital […] Their motivation, their know-how, their capacity to innovate and their attention to clients’ desires constitute the raw material of innovative services […] Their behavior, their social and emotional competence, are a growing factor in the evaluation of their work […] This will no longer be evaluated in terms of number of hours on the job, but on the basis of objectives attained and quality of results. They are entrepreneurs.”

The series of tasks that can’t be delegated to automation form a nebulous cluster of jobs that, because they cannot be occupied by machines, are occupied by any old human – warehousemen, stock people, assembly line workers, seasonal workers, etc. This flexible, undifferentiated workforce that moves from one task to the next and never stays long in a business can no longer even consolidate itself as a force, being outside the center of the production process and employed to plug the holes of what has not yet been mechanized, as if pulverized in a multitude of interstices. The temp is the figure of the worker who is no longer a worker, who no longer has a trade – but only abilities that he sells where he can – and whose very availability is also a kind of work.

On the margins of this workforce that is effective and necessary for the functioning of the machine, is a growing majority that has become superfluous, that is certainly useful to the flow of production but not much else, which introduces the risk that, in its idleness, it will set about sabotaging the machine. The menace of a general demobilization is the specter that haunts the present system of production. Not everybody responds to the question “why work?” in the same way as this ex-welfare recipient: “for my well-being. I have to keep myself busy.” There is a serious risk that we will end up finding a job in our very idleness. This floating population must somehow be kept occupied. But to this day they have not found a better disciplinary method than wages. It’s therefore necessary to pursue the dismantling of “social gains” so that the most restless ones, those who will only surrender when faced with the alternative between dying of hunger or stagnating in jail, are lured back to the bosom of wage-labor. The burgeoning slave trade in “personal services” must continue: cleaning, catering, massage, domestic nursing, prostitution, tutoring, therapy, psychological aid, etc. This is accompanied by a continual raising of the standards of security, hygiene, control, and culture, and by an accelerated recycling of fashions, all of which establish the need for such services. In Rouen, we now have “human parking meters:” someone who waits around on the street and delivers you your parking slip, and, if it’s raining, will even rent you an umbrella.

The order of work was the order of a world. The evidence of its ruin is paralyzing to those who dread what will come after. Today work is tied less to the economic necessity of producing goods than to the political necessity of producing producers and consumers, and of preserving by any means necessary the order of work. Producing oneself is becoming the dominant occupation of a society where production no longer has an object: like a carpenter who’s been evicted from his shop and in desperation sets about hammering and sawing himself. All these young people smiling for their job interviews, who have their teeth whitened to give them an edge, who go to nightclubs to boost the company spirit, who learn English to advance their careers, who get divorced or married to move up the ladder, who take courses in leadership or practice “self-improvement” in order to better “manage conflicts” – “the most intimate ’self-improvement’”, says one guru, “will lead to increased emotional stability, to smoother and more open relationships, to sharper intellectual focus, and therefore to a better economic performance.” This swarming little crowd that waits impatiently to be hired while doing whatever it can to seem natural is the result of an attempt to rescue the order of work through an ethos of mobility. To be mobilized is to relate to work not as an activity but as a possibility. If the unemployed person removes his piercings, goes to the barber and keeps himself busy with “projects,” if he really works on his “employability,” as they say, it’s because this is how he demonstrates his mobility. Mobility is this slight detachment from the self, this minimal disconnection from what constitutes us, this condition of strangeness whereby the self can now be taken up as an object of work, and it now becomes possible to sell oneself rather than one’s labor power, to be remunerated not for what one does but for what one is, for our exquisite mastery of social codes, for our relational talents, for our smile and our way of presenting ourselves. This is the new standard of socialization. Mobility brings about a fusion of the two contradictory poles of work: here we participate in our own exploitation, and all participation is exploited. Ideally, you are yourself a little business, your own boss, your own product. Whether one is working or not, it’s a question of generating contacts, abilities, networking, in short: “human capital.” The planetary injunction to mobilize at the slightest pretext – cancer, “terrorism,” an earthquake, the homeless – sums up the reigning powers’ determination to maintain the reign of work beyond its physical disappearance.

The present production apparatus is therefore, on the one hand, a gigantic machine for psychic and physical mobilization, for sucking the energy of humans that have become superfluous, and, on the other hand, it is a sorting machine that allocates survival to conformed subjectivities and rejects all “problem individuals,” all those who embody another use of life and, in this way, resist it. On the one hand, ghosts are brought to life, and on the other, the living are left to die. This is the properly political function of the contemporary production apparatus.

To organize beyond and against work, to collectively desert the regime of mobility, to demonstrate the existence of a vitality and a discipline precisely in demobilization, is a crime for which a civilization on its knees is not about to forgive us. In fact, it’s the only way to survive it.

Fourth Circle

“More simple, more fun, more mobile, more secure!”

We’ve heard enough about the “city” and the “country,” and particularly about the supposed ancient opposition between the two. From up close or from afar, what surrounds us looks nothing like that: it is one single urban cloth, without form or order, a bleak zone, endless and undefined, a global continuum of museum-like city centers and natural parks, of enormous suburban housing developments and massive agricultural projects, industrial zones and subdivisions, country inns and trendy bars: the metropolis. Certainly the ancient city existed, as did the cities of medieval and modern times. But there is no such thing as a metropolitan city. All territory is synthesized within the metropolis. Everything occupies the same space, if not geographically then through the intermeshing of its networks.

It’s because the city has finally disappeared that it has now become fetishized, as history. The factory buildings of Lille become concert halls. The rebuilt concrete core of Le Havre is now a UNESCO World Heritage sire. In Beijing, the hutongs surrounding the Forbidden City were demolished, replaced by fake versions, placed a little farther out, on display for sightseers. In Troyes they paste half-timber facades onto cinderblock buildings, a type of pastiche that resembles the Victorian shops at Disneyland Paris more than anything else. The old historic centers, once hotbeds of revolutionary sedition, are now wisely integrated into the organizational diagram of the metropolis. They’ve been given over to tourism and conspicuous consumption. They are the fairy-tale commodity islands, propped up by their expos and decorations, and by force if necessary. The oppressive sentimentality of every “Christmas Village” is offset by ever more security guards and city patrols. Control has a wonderful way of integrating itself into the commodity landscape, showing its authoritarian face to anyone who wants to see it. It’s an age of fusions, of muzak, telescoping police batons and cotton candy. Equal parts police surveillance and enchantement!

This taste for the “authentic,” and for the control that goes with it, is carried by the petty bourgeoisie through their colonizing drives into working class neighborhoods. Pushed out of the city centers, they find on the frontiers the kind of “neighborhood feeling” they missed in the prefab houses of suburbia. In chasing out the poor people, the cars, and the immigrants, in making it tidy, in getting rid of all the germs, the petty bourgeoisie pulverizes the very thing it came looking for. A police officer and a garbage man shake hands in a picture on a town billboard, and the slogan reads: “Montauban – Clean City.”

The same sense of decency that obliges urbanists to stop speaking of the “city” (which they destroyed) and instead to talk of the “urban,” should compel them also to drop “country” (since it no longer exists). The uprooted and stressed-out masses are instead shown a countryside, a vision of the past that’s easy to stage now that the country folk have been so depleted. It is a marketing campaign deployed on a “territory” in which everything must be valorized or reconstituted as national heritage. Everywhere it’s the same chilling void, reaching into even the most remote and rustic corners.

The metropolis is this simultaneous death of city and country. It is the crossroads where all the petty bourgeois come together, in the middle of this middle class that stretches out indefinitely, as much a result of rural flight as of urban sprawl. To cover the planet with glass would fit perfectly the cynicism of contemporary architecture. A school, a hospital, or a media center are all variations on the same theme: transparency, neutrality, uniformity. These massive, fluid buildings are conceived without any need to know what they will house. They could be here as much as anywhere else. What to do with all the office towers at La Défense in Paris, the apartment blocks of Lyon’s La Part Dieu, or the shopping complexes of EuraLille? The expression “flambant neuf” perfectly captures their destiny. A Scottish traveler testifies to the unique attraction of the power of fire, speaking after rebels had burned the Hôtel de Ville in Paris in May, 1871:

“Never could I have imagined anything so beautiful. It’s superb. I won’t deny that the people of the Commune are frightful rogues. But what artists! And they were not even aware of their own masterpiece! […] I have seen the ruins of Amalfi bathed in the azure swells of the Mediterranean, and the ruins of the Tung-hoor temples in Punjab. I’ve seen Rome and many other things. But nothing can compare to what I have seen here tonight before my very eyes.”

There still remain some fragments of the city and some traces of the country caught up in the metropolitan mesh. But vitality has taken up quarters in the so-called “problem” neighborhoods. It’s a paradox that the places thought to be the most uninhabitable turn out to be the only ones still in some way inhabited. An old squatted shack still feels more lived in than the so-called luxury apartments where it is only possible to set down the furniture and get the décor just right while waiting for the next move. Within many of today’s megalopolises, the shantytowns are the last living and livable areas, and also, of course, the most deadly. They are the flip-side of the electronic décor of the global metropolis. The dormitory towers in the suburbs north of Paris, abandoned by a petty bourgeoisie that went off hunting for swimming pools, have been brought back to life by mass unemployment and now radiate more energy than the Latin Quarter. In words as much as fire.

The conflagration of November 2005 was not a result of extreme dispossession, as it is often portrayed. It was, on the contrary, a complete possession of a territory. People can burn cars because they are pissed off, but to keep the riots going for a month, while keeping the police in check – to do that you have to know how to organize, you have to establish complicities, you have to know the terrain perfectly, and share a common language and a common enemy. Mile after mile and week after week, the fire spread. New blazes responded to the original ones, appearing where they were least expected. Rumors can’t be wiretapped.

The metropolis is a terrain of constant low-intensity conflict, in which the taking of Basra, Mogadishu, or Nablus mark points of culmination. For a long time, the city was a place for the military to avoid, or if anything, to besiege; but the metropolis is perfectly compatible with war. Armed conflict is only a moment in its constant reconfiguration. The battles led by the great powers resemble a kind of never-ending police work in the black holes of the metropolis, “whether in Burkina Faso, in the South Bronx, in Kamagasaki, in Chiapas, or in La Courneuve.” No longer undertaken in view of victory or peace, or even the re-establishment of order, such “interventions” continue a security operation that is always already at work. War is no longer a distinct event in time, but instead diffracts into a series of micro-operations, by both military and police, to ensure security.

The police and the army are evolving in parallel and in lock-step. A criminologist requests that the national riot police reorganize itself into small, professionalized, mobile units. The military academy, cradle of disciplinary methods, is rethinking its own hierarchical organization. For his infantry battalion a NATO officer employs a

“participatory method that involves everyone in the analysis, preparation, execution, and evaluation of an action. The plan is considered and reconsidered for days, right through the training phase and according to the latest intelligence […] There is nothing like group planning for building team cohesion and morale.”

The armed forces don’t simply adapt themselves to the metropolis, they produce it. Thus, since the battle of Nablus, Israeli soldiers have become interior designers. Forced by Palestinian guerrillas to abandon the streets, which had become too dangerous, they learned to advance vertically and horizontally into the heart of the urban architecture, poking holes in walls and ceilings in order to move through them. An officer in the Israel Defense Forces, and a graduate in philosophy, explains: “the enemy interprets space in a traditional, classical manner, and I do not want to obey this interpretation and fall into his traps. […] I want to surprise him! This is the essence of war. I need to win […] This is why that we opted for the methodology of moving through walls […] Like a worm that eats its way forward.” Urban space is more than just the theater of confrontation, it is also the means. This echoes the advice of Blanqui who recommended (in this case for the party of insurrection) that the future insurgents of Paris take over the houses on the barricaded streets to protect their positions, that they should bore holes in the walls to allow passage between houses, break down the ground floor stairwells and poke holes in the ceilings to defend themselves against potential attackers, rip out the doors and use them to barricade the windows, and turn each floor into a gun turret.

The metropolis is not just this urban pile-up, this final collision between city and country. It is also a flow of beings and things, a current that runs through fiber-optic networks, through high-speed train lines, satellites, and video surveillance cameras, making sure that this world never stops running straight to its ruin. It is a current that would like to drag everything along in its hopeless mobility, to mobilize each and every one of us. Where information pummels us like some kind of hostile force. Where the only thing left to do is run. Where it becomes hard to wait, even for the umpteenth subway train.

With the proliferation of means of movement and communication, and with the lure of always being elsewhere, we are continuously torn from the here and now. Hop on an intercity or commuter train, pick up a telephone – in order to be already gone. Such mobility only ever means uprootedness, isolation, exile. It would be insufferable if it weren’t always the mobility of a private space, of a portable interior. The private bubble doesn’t burst, it floats around. The process of cocooning is not going away, it is merely being put into motion. From a train station, to an office park, to a commercial bank, from one hotel to another, there is everywhere a foreignness, a feeling so banal and so habitual it becomes the last form of familiarity. Metropolitan excess is this capricious mixing of definite moods, indefinitely recombined. The city centers of the metropolis are not clones of themselves, but offer instead their own auras; we glide from one to the next, selecting this one and rejecting that one, to the tune of a kind of existential shopping trip among different styles of bars, people, designs, or playlists. “With my mp3 player, I’m the master of my world.” To cope with the uniformity that surrounds us, our only option is to constantly renovate our own interior world, like a child who constructs the same little house over and over again, or like Robinson Crusoe reproducing his shopkeeper’s universe on a desert island – yet our desert island is civilization itself, and there are billions of us continually washing up on it.

It is precisely due to this architecture of flows that the metropolis is one of the most vulnerable human arrangements that has ever existed. Supple, subtle, but vulnerable. A brutal shutting down of borders to fend off a raging epidemic, a sudden interruption of supply lines, organized blockades of the axes of communication – and the whole facade crumbles, a facade that can no longer mask the scenes of carnage haunting it from morning to night. The world would not be moving so fast if it didn’t have to constantly outrun its own collapse.

The metropolis aims to shelter itself from inevitable malfunction via its network structure, via its entire technological infrastructure of nodes and connections, its decentralized architecture. The internet is supposed to survive a nuclear attack. Permanent control of the flow of information, people and products makes the mobility of the metropolis secure, while its’ tracking systems ensure that no shipping containers get lost, that not a single dollar is stolen in any transaction, and that no terrorist ends up on an airplane. All thanks to an RFID chip, a biometric passport, a DNA profile.

But the metropolis also produces the means of its own destruction. An American security expert explains the defeat in Iraq as a result of the guerrillas’ ability to take advantage of new ways of communicating. The US invasion didn’t so much import democracy to Iraq as it did cybernetic networks. They brought with them one of the weapons of their own defeat. The proliferation of mobile phones and internet access points gave the guerrillas newfound ways to self-organize, and allowed them to become such elusive targets.

Every network has its weak points, the nodes that must be undone in order to interrupt circulation, to unwind the web. The last great European electrical blackout proved it: a single incident with a high-tension wire and a decent part of the continent was plunged into darkness. In order for something to rise up in the midst of the metropolis and open up other possibilities, the first act must be to interrupt its perpetuum mobile. That is what the Thai rebels understood when they knocked out electrical stations. That is what the French anti-CPE protestors understood in 2006 when they shut down the universities with a view toward shutting down the entire economy. That is what the American longshoremen understood when they struck in October, 2002 in support of three hundred jobs, blocking the main ports on the West Coast for ten days. The American economy is so dependent on goods coming from Asia that the cost of the blockade was over a billion dollars per day. With ten thousand people, the largest economic power in the world can be brought to its knees. According to certain “experts,” if the action had lasted another month, it would have produced “a recession in the United States and an economic nightmare in Southeast Asia.”

Fifth Circle

“Less possessions, more connections!”

Thirty years of “crisis,” mass unemployment and flagging growth, and they still want us to believe in the economy. Thirty years punctuated, it is true, by delusionary interludes: the interlude of 1981-83, when we were deluded into thinking a government of the left might make people better off; the “easy money” interlude of 1986-89, when we were all supposed to be playing the market and getting rich; the internet interlude of 1998-2001, when everyone was going to get a virtual career through being well-connected, when a diverse but united France, cultured and multicultural, would bring home every World Cup. But here we are, we’ve drained our supply of delusions, we’ve hit rock bottom and are totally broke, or buried in debt.

We have to see that the economy is not “in” crisis, the economy is itself the crisis. It’s not that there’s not enough work, it’s that there is too much of it. All things considered, it’s not the crisis that depresses us, it’s growth. We must admit that the litany of stock market prices moves us about as much as a Latin mass. Luckily for us, there are quite a few of us who have come to this conclusion. We’re not talking about those who live off various scams, who deal in this or that, or who have been on welfare for the last ten years. Or of all those who no longer find their identity in their jobs and live for their time off. Nor are we talking about those who’ve been swept under the rug, the hidden ones who make do with the least, and yet outnumber the rest. All those struck by this strange mass detachment, adding to the ranks of retirees and the cynically overexploited flexible labor force. We’re not talking about them, although they too should, in one way or another, arrive at a similar conclusion.

We are talking about all of the countries, indeed entire continents, that have lost faith in the economy, either because they’ve seen the IMF come and go amid crashes and enormous losses, or because they’ve gotten a taste of the World Bank. The soft crisis of vocation that the West is now experiencing is completely absent in these places. What is happening in Guinea, Russia, Argentina and Bolivia is a violent and long-lasting debunking of this religion and its clergy. “What do you call a thousand IMF economists lying at the bottom of the sea?” went the joke at the World Bank, – “a good start.” A Russian joke: “Two economists meet. One asks the other: ‘You understand what’s happening?’ The other responds: ‘Wait, I’ll explain it to you.’ ‘No, no,’ says the first, ‘explaining is no problem, I’m an economist, too. What I’m asking is: do you understand?” Entire sections of this clergy pretend to be dissidents and to critique this religion’s dogma. The latest attempt to revive the so-called “science of the economy” – a current that straight-facedly refers to itself as “post autistic economics” – makes a living from dismantling the usurpations, sleights of hand and cooked books of a science whose only tangible function is to rattle the monstrance during the vociferations of the chiefs, giving their demands for submission a bit of ceremony, and ultimately doing what religions have always done: providing explanations. For total misery becomes intolerable the moment it is shown for what it is, without cause or reason.

Nobody respects money anymore, neither those who have it nor those who don’t. When asked what they want to be some day, twenty percent of young Germans answer “artist.” Work is no longer endured as a given of the human condition. The accounting departments of corporations confess that they have no idea where value comes from. The market’s bad reputation would have done it in a decade ago if not for the bluster and fury, not to mention the deep pockets, of its apologists. It is common sense now to see progress as synonymous with disaster. In the world of the economic, everything is in flight, just like in the USSR under Andropov. Anyone who has spent a little time analyzing the final years of the USSR knows very well that the pleas for goodwill coming from our rulers, all of their fantasies about some future that has disappeared without a trace, all of their professions of faith in “reforming” this and that, are just the first fissures in the structure of the wall. The collapse of the socialist bloc was in no way victory of capitalism; it was merely the bankrupting of one of the forms capitalism takes. Besides, the demise of the USSR did not come about because a people revolted, but because the nomenclature was undergoing a process of reconversion. When it proclaimed the end of socialism, a small fraction of the ruling class emancipated itself from the anachronistic duties that still bound it to the people. It took private control of what it already controlled in the name of “everyone.” In the factories, the joke went: “we pretend to work, they pretend to pay us.” The oligarchy replied, “there’s no point, let’s stop pretending!” They ended up with the raw materials, industrial infrastructures, the military-industrial complex, the banks and the nightclubs. Everyone else got poverty or emigration. Just as no one in Andropov’s time believed in the USSR, no one in the meeting halls, workshops and offices believes in France today. “There’s no point,” respond the bosses and political leaders, who no longer even bother to file the edges off the “iron laws of the economy.” They strip factories in the middle of the night and announce the shutdown early next morning. They no longer hesitate to send in anti-terrorism units to shut down a strike, like with the ferries and the occupied recycling center in Rennes. The brutal activity of power today consists both in administering this ruin while, at the same time, establishing the framework for a “new economy.”

And yet there is no doubt that we are cut out for the economy. For generations we were disciplined, pacified and made into subjects, productive by nature and content to consume. And suddenly everything that we were compelled to forget is revealed: that the economy is political. And that this politics is, today, a politics of discrimination within a humanity that has, as a whole, become superfluous. From Colbert to de Gaulle, by way of Napoleon III, the state has always treated the economic as political, as have the bourgeoisie (who profit from it) and the proletariat (who confront it). All that’s left is this strange, middling part of the population, the curious and powerless aggregate of those who take no sides: the petty bourgeoisie. They have always pretended to believe that the economy is a reality-because their neutrality is safe there. Small business owners, small bosses, minor bureaucrats, managers, professors, journalists, middlemen of every sort make up this non-class in France, this social gelatin composed of the mass of all those who just want to live their little private lives at a distance from history and its tumults. This swamp is predisposed to be the champion of false consciousness, half-asleep and always ready to close its eyes on the war that rages all around it. Each clarification of a front in this war is thus accompanied in France by the invention of some new fad. For the past ten years, it was ATTAC and its improbable Tobin tax -a tax whose implementation would require nothing less than a global government-with its sympathy for the “real economy” as opposed to the financial markets, not to mention its touching nostalgia for the state. The comedy lasts only so long before turning into a sham. And then another fad replaces it. So now we have “degrowth“. Whereas ATTAC tried to save economics as a science with its popular education courses, degrowth preserves the economic as a morality. There is only one alternative to the coming apocalypse: reduce growth. Consume and produce less. Become joyously frugal. Eat organic, ride your bike, stop smoking, and pay close attention to the products you buy. Be content with what’s strictly necessary. Voluntary simplicity. “Rediscover true wealth in the blossoming of convivial social relations in a healthy world.” “Don’t use up our natural capital.” Work toward a “healthy economy.” “No regulation through chaos.” “Avoid a social crisis that would threaten democracy and humanism.” Simply put: become economical. Go back to daddy’s economy, to the golden age of the petty bourgeoisie: the 1950s. “When an individual is frugal, property serves its function perfectly, which is to allow the individual to enjoy his or her own life sheltered from public existence, in the private sanctuary of his or her life.”

A graphic designer wearing a handmade sweater is drinking a fruity cocktail with some friends on the terrace of an “ethnic” café. They’re chatty and cordial, they joke around a bit, they make sure not to be too loud or too quiet, they smile at each other, a little blissfully: we are so civilized. Afterwards, some of them will go work in the neighborhood community garden, while others will dabble in pottery, some Zen Buddhism, or in the making of an animated film. They find communion in the smug feeling that they constitute a new humanity, wiser and more refined than the previous one. And they are right. There is a curious agreement between Apple and the degrowth movement about the civilization of the future. Some people’s idea of returning to the economy of yesteryear offers others the convenient screen behind which a great technological leap forward can be launched. For in history there is no going back. Any exhortation to return to the past is only the expression of one form of consciousness of the present, and rarely the least modern. It is not by chance that degrowth is the banner of the dissident advertisers of the magazine Casseurs de Pub. The inventors of zero growth-the Club of Rome in 1972-were themselves a group of industrialists and bureaucrats who relied on a research paper written by cyberneticians at MIT.

This convergence is hardly a coincidence. It is part of the forced march towards a modernized economy. Capitalism got as much as it could from undoing all the old social ties, and it is now in the process of remaking itself by rebuilding these same ties on its own terms. Contemporary metropolitan social life is its incubator. In the same way, it ravaged the natural world and is driven by the fantasy that it can now be reconstituted as so many controlled environments, furnished with all the necessary sensors. This new humanity requires a new economy that would no longer be a separate sphere of existence but, on the contrary, its very tissue, the raw material of human relations; it requires a new definition of work as work on oneself, a new definition of capital as human capital, a new idea of production as the production of relations, and consumption as the consumption of situations; and above all a new idea of value that would encompass all of the qualities of beings. This burgeoning “bioeconomy” conceives the planet as a closed system to be managed and claims to establish the foundations for a science that would integrate all the parameters of life. Such a science threatens to make us miss the good old days when unreliable indices like GDP growth were supposed to measure the well-being of a people-for at least no one believed in them.

“Revalorize the non-economic aspects of life” is the slogan shared by the degrowth movement and by capital’s reform program. Eco-villages, video-surveillance cameras, spirituality, biotechnologies and sociability all belong to the same “civilizational paradigm” now taking shape, that of a total economy rebuilt from the ground up. Its intellectual matrix is none other than cybernetics, the science of systems-that is, the science of their control. In the 17th century it was necessary, in order to completely impose the force of economy and its ethos of work and greed, to confine and eliminate the whole seamy mass of layabouts, liars, witches, madmen, scoundrels and all the other vagrant poor, a whole humanity whose very existence gave the lie to the order of interest and continence. The new economy cannot be established without a similar screening of subjects and zones singled out for transformation. The chaos that we constantly hear about will either provide the opportunity for this screening, or for our victory over this odious project.

Sixth Circle

“The environment is an industrial challenge.”

Ecology is the discovery of the decade. For the last thirty years we’ve left it up to the environmentalists, joking about it on Sunday so that we can act concerned again on Monday. And now it’s caught up to us, invading the airwaves like a hit song in summertime, because it’s 68 degrees in December.

One quarter of the fish species have disappeared from the ocean. The rest won’t last much longer.

Bird flu alert: we are given assurances that hundreds of thousands of migrating birds will be shot from the sky.

Mercury levels in human breast milk are ten times higher than the legal level for cows. And these lips which swell up after I bite the apple – but it came from the farmer’s market. The simplest gestures have become toxic. One dies at the age of 35 from “a prolonged illness” that’s to be managed just like one manages everything else. We should’ve seen it coming before we got to this place, to pavilion B of the palliative care center.

You have to admit: this whole “catastrophe,” which they so noisily inform us about, it doesn’t really touch us. At least not until we are hit by one of its foreseeable consequences. It may concern us, but it doesn’t touch us. And that is the real catastrophe.

There is no “environmental catastrophe.” The catastrophe is the environment itself. The environment is what’s left to man after he’s lost everything. Those who live in a neighborhood, a street, a valley, a war zone, a workshop – they don’t have an “environment;” they move through a world peopled by presences, dangers, friends, enemies, moments of life and death, all kinds of beings. Such a world has its own consistency, which varies according to the intensity and quality of the ties attaching us to all of these beings, to all of these places. It’s only us, the children of the final dispossession, exiles of the final hour – the ones who come into the world in concrete cubes, pick our fruits at the supermarket, and watch for an echo of the world on television – only we get to have an environment. And there’s no one but us to witness our own annihilation, as if it were just a simple change of scenery, to get indignant about the latest progress of the disaster, to patiently compile its encyclopedia.

What has congealed as an environment is a relationship to the world based on management, which is to say, on estrangement. A relationship to the world wherein we’re not made up just as much of the rustling trees, the smell of frying oil in the building, running water, the hubbub of schoolrooms, the mugginess of summer evenings. A relationship to the world where there is me and then my environment, surrounding me but never really constituting me. We have become neighbors in a planetary co-op owners’ board meeting. It’s difficult to imagine a more complete hell.

No material habitat has ever deserved the name “environment,” except perhaps the metropolis of today. The digitized voices making announcements, tramways with such a 21st century whistle, bluish streetlamps shaped like giant matchsticks, pedestrians done up like failed fashion models, the silent rotation of a video surveillance camera, the lucid clicking of the subway turnstyles supermarket checkouts, office time-clocks, the electronic ambiance of the cyber café, the profusion of plasma screens, express lanes and latex. Never has a setting been so able to do without the souls traversing it. Never has a surrounding been more automatic. Never has a context been so indifferent, and demanded in return – as the price of survival – such equal indifference from us. Ultimately the environment is nothing more than the relationship to the world that is proper to the metropolis, and that projects itself onto everything that would escape it.

It goes like this: they hired our parents to destroy this world, now they’d like to put us to work rebuilding it, and – to top it all off – at a profit. The morbid excitement that animates journalists and advertisers these days as they report each new proof of global warming reveals the steely smile of the new green capitalism, in the making since the 70s, which we waited for at the turn of the century but which never came. Well, here it is! It’s sustainability! Alternative solutions, that’s it too! The health of the planet demands it! No doubt about it anymore, it’s a green scene; the environment will be the crux of the political economy of the 21st century. A new volley of “industrial solutions” comes with each new catastrophic possibility.

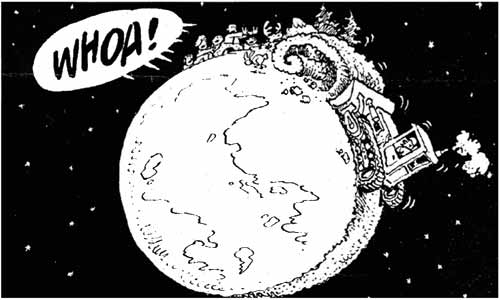

The inventor of the H-bomb, Edward Teller, proposes shooting millions of tons of metallic dust into the stratosphere to stop global warming. NASA, frustrated at having to shelve its idea of an anti-missile shield in the museum of cold war horrors, suggests installing a gigantic mirror beyond the moon’s orbit to protect us from the sun’s now-fatal rays. Another vision of the future: a motorized humanity, driving on bio-ethanol from Sao Paulo to Stockholm; the dream of cereal growers the world over, for it only means converting all of the planet’s arable lands into soy and sugar beet fields. Eco-friendly cars, clean energy, and environmental consulting coexist painlessly with the latest Chanel ad in the pages of glossy magazines.

We are told that the environment has the incomparable merit of being the first truly global problem presented to humanity. A global problem, which is to say a problem that only those who are organized on a global level will be able to solve. And we know who they are. These are the very same groups that for close to a century have been the vanguard of disaster, and certainly intend to remain as such, for the small price of a change of logo. That EDF had the impudence to bring back its nuclear program as the new solution to the global energy crisis says plenty about how much the new solutions resemble the old problems.

From Secretaries of State to the back rooms of alternative cafés, concerns are always expressed in the same words, the same as they’ve always been. We have to get mobilized. This time it’s not to rebuild the country like in the post-war era, not for the Ethiopians like in the 1980s, not for employment like in the 1990s. No, this time it’s for the environment. It will thank you for it. Al Gore and degrowth movement stand side by side with the eternal great souls of the Republic to do their part in resuscitating the little people of the Left and the well-known idealism of youth. Voluntary austerity writ large on their banner, they work benevolently to make us compliant with the “coming ecological state of emergency.” The round and sticky mass of their guilt lands on our tired shoulders, coddling us to cultivate our garden, sort out our trash, and eco-compost the leftovers of this macabre feast.

Managing the phasing out of nuclear power, excess CO2 in the atmosphere, melting glaciers, hurricanes, epidemics, global over-population, erosion of the soil, mass extinction of living species… this will be our burden. They tell us, “everyone must do their part,” if we want to save our beautiful model of civilization. We have to consume a little less in order to be able to keep consuming. We have to produce organically in order to keep producing. We have to control ourselves in order to go on controlling. This is the logic of a world straining to maintain itself whilst giving itself an air of historical rupture. This is how they would like to convince us to participate in the great industrial challenges of this century. And in our bewilderment we’re ready to leap into the arms of the very same ones who presided over the devastation, in the hope that they will get us out of it.

Ecology isn’t simply the logic of a total economy; it’s the new morality of capital. The system’s internal state of crisis and the rigorous screening that’s underway demand a new criterion in the name of which this screening and selection will be carried out. From one era to the next, the idea of virtue has never been anything but an invention of vice. Without ecology, how could we justify the existence of two different food regimes, one “healthy and organic” for the rich and their children, and the other notoriously toxic for the plebes, whose offspring are damned to obesity. The planetary hyper-bourgeoisie wouldn’t be able to make their normal lifestyle seem respectable if its latest caprices weren’t so scrupulously “respectful of the environment.” Without ecology, nothing would have enough authority to gag any and all objections to the exorbitant progress of control.

Tracking, transparency, certification, eco-taxes, environmental excellence, and the policing of water, all give us an idea of the coming state of ecological emergency. Everything is permitted to a power structure that bases its authority in Nature, in health and in well-being.

“Once the new economic and behavioral culture has become common practice, coercive measures will doubtless fall into disuse of their own accord.” You’d have to have all the ridiculous aplomb of a TV crusader to maintain such a frozen perspective and in the same breath incite us to feel sufficiently “sorry for the planet” to get mobilized, whilst remaining anesthetized enough to watch the whole thing with restraint and civility. The new green-asceticism is precisely the self-control that is required of us all in order to negotiate a rescue operation where the system has taken itself hostage. From now on, it’s in the name of environmentalism that we must all tighten our belts, just as we did yesterday in the name of the economy. The roads could certainly be transformed into bicycle paths, we ourselves could perhaps, to a certain degree, be grateful one day for a guaranteed income, but only at the price of an entirely therapeutic existence. Those who claim that generalized self-control will spare us from an environmental dictatorship are lying: the one will prepare the way for the other, and we’ll end up with both.

As long as there is Man and Environment, the police will be there between them.

Everything about the environmentalist’s discourse must be turned upside-down. Where they talk of “catastrophes” to label the present system’s mismanagement of beings and things, we only see the catastrophe of its all too perfect operation. The greatest wave of famine ever known in the tropics (1876-1879) coincided with a global drought, but more significantly, it also coincided with the apogee of colonization. The destruction of the peasant’s world and of local alimentary practices meant the disappearance of the means for dealing with scarcity. More than the lack of water, it was the effect of the rapidly expanding colonial economy that littered the Tropics with millions of emaciated corpses. What presents itself everywhere as an ecological catastrophe has never stopped being, above all, the manifestation of a disastrous relationship to the world. Inhabiting a nowhere makes us vulnerable to the slightest jolt in the system, to the slightest climactic risk. As the latest tsunami approached and the tourists continued to frolic in the waves, the islands’ hunter-gatherers hastened to flee the coast, following the birds. Environmentalism’s present paradox is that under the pretext of saving the planet from desolation it merely saves the causes of its desolation.

The normal functioning of the world usually serves to hide our state of truly catastrophic dispossession. What is called “catastrophe” is no more than the forced suspension of this state, one of those rare moments when we regain some sort of presence in the world. Let the petroleum reserves run out earlier than expected; let the international flows that regulate the tempo of the metropolis be interrupted, let us suffer some great social disruption and some great “return to savagery of the population,” a “planetary threat,” the “end of civilization!” Either way, any loss of control would be preferable to all the crisis management scenarios they envision. When this comes, the specialists in sustainable development won’t be the ones with the best advice. It’s within the malfunction and short-circuits of the system that we find the elements of a response whose logic would be to abolish the problems themselves. Among the signatory nations to the Kyoto Protocol, the only countries that have fulfilled their commitments, in spite of themselves, are the Ukraine and Romania. Guess why. The most advanced experimentation with “organic” agriculture on a global level has taken place since 1989 on the island of Cuba. Guess why. And it’s along the African highways, and nowhere else, that auto mechanics has been elevated to a form of popular art. Guess how.

What makes the crisis desirable is that in the crisis the environment ceases to be the environment. We are forced to reestablish contact, albeit a potentially fatal one, with what’s there, to rediscover the rhythms of reality. What surrounds us is no longer a landscape, a panorama, a theater, but something to inhabit, something we need to come to terms with, something we can learn from. We won’t let ourselves be led astray by the one’s who’ve brought about the contents of the “catastrophe.” Where the managers platonically discuss among themselves how they might decrease emissions “without breaking the bank,” the only realistic option we can see is to “break the bank” as soon as possible and, in the meantime, take advantage of every collapse in the system to increase our own strength.