WHO stole the 2020 presidential election? I think the evidence was in our faces every day on the telly. And the perpetrators pulled it off fair and square, just as the kleptocrats among our founding fathers intended. The corporate media pundits were unanimous about who Americans should vote for and enough of the country believed them. In the final stretch they even blacked out a story that would have been widely damaging to the Biden plunderbund and blocked the president’s Tweets, deciding for themselves which news was “real” and which “fake”. Which is their prerogative of course, as costodians of a universally false narrative. Early in his term Trump declared the media to be the American People’s most dangerous enemy. But only the MAGA crowd believed him. Blue America is still making fun of red but who are the bigger fools really?

Tag Archives: Headlines

A “1969 Project” Would Say the Moon Landing Didn’t Happen

The New York Times’ woke campaign “1619 Project” offers restitution for slavery with typical newspaperman philanthropy: the in-kind contribution! Thus “all the news that’s fit to print” gets trimmed by what isn’t centric to the African American experience, not for news in real-time but retroactively! The Grey Lady of Yellow Journalism is courting younger audiences fresh from history courses featuring personages created in their diverse image. As if the past is a pageant of participation awards, purged of the characters whose relevance used to be the making of history. Never mind how you got here, the study of history is now a showcase of what insignificant role you might aspire to when it’s your turn to play a part.

Corporate News Streetwalker Didn’t See That Coming

Local news reporter Alex Bozarjian felt “violated, objectified, and embarrassed” when a passing marathon runner grabbed her butt on live TV. Hopefully we’ll be seeing more of that! Corporate media INDULGES in disrespect and objectification, shouldn’t their representatives be braced for the consequence? Was it a sexual assault? Not of Bozarjian! The grinning runner did that FOR THE CAMERA! It was a slap aimed to denigrate and disrespect the media, and should forewarn every mainstream news hack who presumes their victimized public cannot strike back. Bozarjian’s station says “No woman should have to endure that abuse simply for doing her job.” Doing THAT job — how about ALL of them? Male AND female! Whether fool or knave, unknowing or mendacious, media whores deserve a slap whenever they surface in public. Granted, that slap will probably be more effective delivered in the face. Bozarjian got off easy.

Local news reporter Alex Bozarjian felt “violated, objectified, and embarrassed” when a passing marathon runner grabbed her butt on live TV. Hopefully we’ll be seeing more of that! Corporate media INDULGES in disrespect and objectification, shouldn’t their representatives be braced for the consequence? Was it a sexual assault? Not of Bozarjian! The grinning runner did that FOR THE CAMERA! It was a slap aimed to denigrate and disrespect the media, and should forewarn every mainstream news hack who presumes their victimized public cannot strike back. Bozarjian’s station says “No woman should have to endure that abuse simply for doing her job.” Doing THAT job — how about ALL of them? Male AND female! Whether fool or knave, unknowing or mendacious, media whores deserve a slap whenever they surface in public. Granted, that slap will probably be more effective delivered in the face. Bozarjian got off easy.

Jeffrey Epstein escapes federal jail

Even petty blackmailer extortionists know to warn “if anything happens to me, incriminating evidence will be released to the media.” Billionaire sex offender Jeffrey Epstein is already fading from the news and not one manila envelope has dropped. What does that tell you about what “happened” to Jeffrey Epstein? It didn’t. You might think his suicide was really a murder, but let’s remember he counted the most powerful pervs among his friends. Fat chance any of them wanted their friend and primo procurer killed. Before his suicide, Jeffrey Epstein signed a will, his last legal opportunity to do so, then he did El Chapo one better. With allegedly dozing guards (one of them a temp with a shorter personnel record, maybe more easily impersonated), and under faulty surveillance cameras, El Epstein disappeared from federal custody into his own self-financed witness protection plan. What’s it take? An anesthetic cocktail for the short gurney ride, not that many parties to pay off or knock off later, your body is released to an unnamed “Epstein Associate,” and it’s party time again at your Virgin Island! Pretty damn obvious.

Kimya Dawson knows from where protest must burst: At the Seams.

Kimya Dawson not only nailed the essence of protests for #BlackLivesMatter. She knew in which direction the protest marches needed to push. Toward our system’s seams. If you are having trouble finding the lyrics of her song about HANDS UP DON’T SHOOT I CAN’T BREATH, it’s because it’s called At the Seams.

I’ve taken the liberty to reformat Dawson’s brilliant lyrics to unpack her references and simulate her cadence.

AT THE SEAMS by Kimya Dawson

1.

Left hands hold the leashes

and the right hands hold the torches,

And Grandpas holding shotguns

swing on porch swings hung on porches,

And the Grandmas in their gardens

plant more seeds to cut their losses,

And the poachers,

with the pooches

and the nooses,

preheat crosses.And the pooches see the Grandpas

and they bare their teeth and growl,

While their owners turn their noses up

like they smell something foul,

And they fumble with their crosses

and they start to mumble curses,

And they plot ways

to get Grandpas

off of porches

into hearses.But the Grandpas on the porches

are just scarecrows holding toys,

And the Grandmas in the gardens

are papier-mâché decoys,

While the real Grandmas and Grandpas

are with all the girls and boys

Marching downtown to the City Hall

to make a lot of noise,

Saying:Hands up. Don’t shoot. I can’t breathe.

BLACK LIVES MATTER. No justice No Peace.

I know that we can overcome because I had a dream-

A dream we tore this racist broken system apart at the seams.2.

Sometimes it seems like

we’ve reached the end of the road

We’ve seen cops and judges sleep together

wearing long white robes.

And they put their white hoods up,

Try to take the black hoods down,

And they don’t plan on stopping

til we’re all in the ground.Til we’re dead in the ground

or we’re incarcerated

‘Cause prison’s

a big business form

of enslavement

Plantations that profit

on black folks in cages

They’ll break our backs

and keep the wages.It’s outrageous that there’s no place

we can feel safe in this nation

Not in our cars, Not at the park,

Not in subway stations,

Not at church, The pool, The store,

Not asking for help,

Not walking down the street,

So we’ve gotta scream and yell:Hands up. Don’t shoot. I can’t breathe.

BLACK LIVES MATTER. No justice No Peace.

I know that we can overcome because I had a dream-

A dream we tore this racist broken system apart at the seams.3.

You tweet me my own lyrics,

Tell me to stop

Letting a few bad apples

ruin the bunch.

Don’t minimize the fight

comparing apples to cops

This is about the orchard’s poisoned roots,

not loose fruits in a box.Once the soil’s been spoiled,

the whole crop’s corrupt.

That’s why we need the grassroots

working from the ground up.

And we look to Black Twitter,

to stay woke and get some truth,

‘Stead of smiling cops

and black mugshots

from biased corporate news.‘Cause if you steal cigarillos,

or you sell loose cigarettes,

Or you forget your turn signal,

will they see your skin as a threat?

Will they KILL you, And then SMEAR you,

And COVER IT UP and LIE?

Will they call it “self defense”?

Will they call it “suicide”?Hands up. Don’t shoot. I can’t breathe.

BLACK LIVES MATTER. No justice No Peace.

I know that we can overcome because I had a dream-

A dream we tore this racist broken system apart at the seams.4.

Decades of cultivation start

from tiny seeds that were once planted.

And we mustn’t take the gardens that

our elders grew for granted,

Though it is up to our youth

how new rows sown are organized,

Because movements can’t keep moving

if old and unsharpened eyes

Can’t see the need to hear

what those on the ground hafta say,

In Ferguson and Cleveland,

Staten Island, The East Bay,

Charleston, Phoenix,

Detroit, Sanford Waller,

Seattle, Los Angeles,

Chicago, Baltimore.Climbing flagpoles, Taking bridges,

Locked together to the BART,

Speaking up about injustice

in our music and our art,

Storming stages to ask candidates

when they’re gonna start

Really DIRECTLY addressing issues

BREAKING OUR HEARTS.Hands up. Don’t shoot. I can’t breathe.

BLACK LIVES MATTER. No justice No Peace.

I know that we can overcome because I had a dream-

A dream we tore this racist broken system apart at the seams.Hands up. Don’t shoot. I can’t breathe.

BLACK LIVES MATTER. No justice No Peace.

I know that we can overcome because I had a dream-

A dream we tore this racist broken system apart at the seams.5.

And if the altars are torn down,

we’ll just keep on placing flowers

For the boy whose body was in the road

FOR MORE THAN FOUR HOURS.

We will honor the dead

of every age and every gender

‘Cause we can’t just have it be

the brothers’ names that we remember.Oh black boys with skateboards,

and black boys with hoodies,

And little black girls who

are on the couch sleeping,

And all of the black trans

women massacred,

Too many black folks killed and brutalized,

And there’s no justice served.After the lynchings of our people

by the murderous police,

Who stand like hunters ’round their prey

gasping helpless in the street,

Feet from the TEEN SISTER they tackled

and locked handcuffed in the car,

Feet from her TWELVE YEAR OLD BROTHER DYING —WHILE NO ONE DID CPR…

6.

And we’ll keep on planting flowers,

and we’ll fight until the day

That we don’t have to pick them all

to put them all on graves.

Yeah we’ll keep planting flowers

and we’ll fight until the day

That we don’t have to pick them all

to put them all on graves.Hands up. Don’t shoot. I can’t breathe.

BLACK LIVES MATTER. No justice No Peace.

I know that we can overcome because I had a dream-

A dream we tore this racist broken system apart at the seams.

CSPD Intelligence doesn’t have much

COLORADO SPRINGS, COLO- Like the term Military Intelligence, “police intelligence” is an oxymoron. At least that’s the old joke. Wednesday’s hearing about the CSPD’s undercover operation against the Colo. Springs Socialists reinforced the adage. The good news is that Metro VNI, that is, Vice Narcotics & Intelligence, doesn’t have much intelligence, as in smarts, haha, OR constructive data. The impetus of CSPD’s efforts to infiltrate local activists has been to track ANTIFA, a nefarious worldwide anti-fascist organization apparently. Lieutenant Mark Comte, who heads Metro-VNI, testified to what they know so far. ANTIFA members wear black and cover their faces. When protesters do that, they’re Antifa.

COLORADO SPRINGS, COLO- Like the term Military Intelligence, “police intelligence” is an oxymoron. At least that’s the old joke. Wednesday’s hearing about the CSPD’s undercover operation against the Colo. Springs Socialists reinforced the adage. The good news is that Metro VNI, that is, Vice Narcotics & Intelligence, doesn’t have much intelligence, as in smarts, haha, OR constructive data. The impetus of CSPD’s efforts to infiltrate local activists has been to track ANTIFA, a nefarious worldwide anti-fascist organization apparently. Lieutenant Mark Comte, who heads Metro-VNI, testified to what they know so far. ANTIFA members wear black and cover their faces. When protesters do that, they’re Antifa.

Iraq War embed Rob McClure, witness to war crimes he didn’t report, suffers phantom pain in gonads he never had.

DENVER, COLORADO- Today Occupy Denver political prisoner Corey Donahue was given a nine month sentence for a 2011 protest stunt. Judge Nicole Rodarte’s unexpected harsh sentence came after the court read the victim statement of CBS4 cameraman Rob McClure, who said he still feels the trauma of the uninvited “cupping [of his] balls” while he was filming the 2011 protest encampment at the state capitol. Donahue admits that McClure was the target of a “nut-tap”, but insists it was feigned, as occupiers demonstrated their disrespect to the corporate news crews who were intent on demonizing the homeless participants even as Denver riot police charged the park. Though a 2012 jury convicted Donahue of misdemeanor unwanted sexual contact, witnesses maintain there was no physical contact.

Of course simply the implication of contact would have humiliated McClure in front of the battalion of police officers amused by the antic. That’s authentic sexual trauma, just as a high school virgin is violated when a braggart falsely claims to have of engaged them in sexual congress. Donahue was wrong, but how wrong? Can professionals who dish it out claim infirmity when the tables are turned?

Ultimately the joke was on Donahue, because his mark turned out to be far more vulnerable than his dirty job would have suggested. The CBS4 cameraman who Donahue picked on was a louse’s louse.

Off limits?

While some might assert there is no context which would excuse touching a stranger’s genital region, I’m not sure the rule of no hitting below the belt is a civility to which folks facing riot cops are in accord. Protesters can’t shoot cops, they can’t spit at cops, in fact protesters have to pull all their punches. Some would have you believe demonstrators should do no more than put daisies in police gun barrels, all the while speaking calmly with only pleasant things to say.

Let me assure you, simply to defy police orders is already a humiliation for police. What’s some pantomimed disrespect? Humiliating riot cops is the least unarmed demonstrators can do against batons and shields and pepper spray. Should the authorities’ private parts be off limits for a public’s expression of discontent? Jocks wear jock straps precisely because private parts aren’t off sides.

It’s tempting to imagine that all cops are human beings who can be turned from following orders to joining in protestations of injustice and inequity. This is of course nonsense. But it’s even more delusional to think corporate media cameras and reporters will ever take a sympathetic line to the travails of dissidents. Media crews exploit public discontent just as riot cops enjoy the overtime. Media crews gather easy stories of compelling interest from interviewees eager to have their complaints be understood.

Corey Donahue

On October 15, 2011, Rob McClure turned his camera off when the narrative wasn’t fitting the derogatory spin he wanted to put on the homeless feeding team which manned Occupy Denver’s kitchen, dubbed “The Thunderdome.” Donahue observed the cameraman’s deliberate black out of the savory versus the unsavory and reciprocated with the crowd pleasing nut-tap. In the midst of this circus, Colorado State Troopers, METRO SWAT, and city riot police charged the encampment and made two dozen arrests.

It was hours later, perhaps after reviewing police surveillance footage, that McClure conferred with police commanders and agreed to press charges for the nut-tap. Corey Donahue was one of the high visibility leaders of the crowd. He’d been involved in multiple arrests, but this time his bond would be higher and harder to post because instead of the usual anti-protest violations, Donahue would be charged with sex crime.

Ultimately Donahue sought political asylum in South America rather than face having to report for the rest of his life as a sex offender. The offense was only a misdemeanor and his trial was a miscarriage of justice. Attorney friends later convinced Donahue to return to the US because this crime was arguably not sex related and was likely to be overturned on appeal. Likewise, a sentence was unlikely to exceed time served as the “nut-tap” paled in comparison to the police brutality and excessive force which has since ensued. Neither Judge Rodarte or victim Rob McClure got the memo, and it wasn’t the first time McClure failed to frame public outcry in the context of brutal militarized repression.

It turns out McClure’s own self respect was probably way too fragile to have ventured to cast stones at the slovenly homeless occupiers.

Rob McClure

Cameraman Robert McClure had been an embedded reporter in Iraq in 2004. You might expect such a experience to have toughened him up, or expanded his empathy for critics of US authoritarian brutality, but that is to underestimate the culpability of the corporate media war drum beaters.

And McClure’s guilt ran deeper that that. According to his CBS4 bio, McClure was reporting from a major military detention center. It turns out McClure covered Abu Fucking Ghraib. In 2004 McClure’s assignment was to distort what happened there as rogue misconduct. No thanks to fuckers like McClure, the Abu Ghraib techniques were later confirmed to be standard protocol. The US torture and humiliation of prisoners was systemic.

McClure’s coverage for CBS4 specifically glorified Dr. Dave Hnida, otherwise a family physician from Littleton, but in the service of the military as a battlefield surgeon assigned to treat prisoners of war. While it sounds commendatory to attend to the health of our sworn adversaries, in practice that job involves most commonly reviving prisoners being subjected to interrogation. Hnida’s task was to keep subjects conscious for our extended depredations. Medical colleagues call those practitioners “torture docs”. They shouldn’t be celebrated. They should lose their medical licenses.

So that’s the Rob McClure who wrote Judge Rodarte to say that after all these years, having witnessed unthinkable horror and sadistic injustice, while still spinning stories to glorify American soldiers and killer cops and power-tripping jailers, the memory of Corey Donahue’s prank made his balls hurt.

Denver used protection orders to curb mobility of Occupy protesters in 2011

DENVER, COLORADO- Activist Corey Donahue’s 11-11-2011 protest case is still outstanding. The recently surrendered fugitive is charged with inciting a riot in the first months of the Occupy Denver encampment, when supporters crowded a police cruiser and began to rock it in protest of Corey’s third arrest. Clouding this nostalgic look back at DPD’s mishandling of mass demonstrations are the quasi-legal steps the city took to constrain the protest.

It turns out Corey’s felony riot charges were used to convince a Denver court to grant protection orders to two state troopers who considered themselves personal victims of Occupy Denver’s assertive tactics. As a resut, Corey was prevented from leading demonstrations into areas when those officers were deployed, and he didn’t know which those officers were.

The measure was of dubious legality and so far remains shrouded in disinformation. Were two officers “seriously injured”, as news outlets reported, in the so-called riot of Nov 11? Except for their official statement, no evidence was ever provided by DPD. What were the injuries and who were the officers?

Can police invoke the protection of a blanket injunction to stop public demonstrations whenever they want? Can a police department enforce protection orders and pretend its subjects can remain anonymous? These are the questions which Denver police face as they push charges against one of their most outspoken antagonists.

Can law enforcement officers unknown to a defendant file for restraining orders against the public they serve and protect? Can police require that ordinary citizens maintain a prescribed distance from them in a public space?

Encamped on the grounds of the capitol, at the peak of an ongoing protest movement, Corey Donahue was in no position to push back with a legal challenge.

Denver has since used an even more abusive method, designating “area restrictions” to keep active protest leaders out of places like the state capitol, Civic Center Park, and 16th Street Mall. DPD cite the arrestees’ repeated arrests as justification. This probation stipulation may be applicable for criminal recidivists, in particular domestic violence abusers, but it is hardly constitutional when applied to free speech. Denver’s practice hasn’t been challenged yet, for want of sympathetic plaintiffs.

Giving police protection orders, to prevent specific demonstrators from assembling near police lines, would seem to fall in a similar category of judicial misconduct.

Who is this El Paso Sheriffs undercover infiltrator provocateur? We don’t care!

COLO. SPRINGS– Lawyers for the city are fighting defense team efforts to expose who, how, when and why local law enforcement agencies infiltrated a campus political activist group. The 2017 undercover operation was revealed in CSPD bodycam videos, but city courthouse lawyers and judges are preventing the evidence from being made public.

COLO. SPRINGS– Lawyers for the city are fighting defense team efforts to expose who, how, when and why local law enforcement agencies infiltrated a campus political activist group. The 2017 undercover operation was revealed in CSPD bodycam videos, but city courthouse lawyers and judges are preventing the evidence from being made public.

Alerted to the October 17 evidentiary hearing meant to shed light on the bodycam video, journalists and news crews instead witnessed stonewalling by city attorneys but made to look like a disorganized defense. They saw municipal Judge Kristen Hoffecker blame the defendants for not submitting to a sham proceding, when the judge should have confessed that the defense’s subpoenas had not been honored.

Today the city learned that our defense team went around them and served the subpoenas directly, requiring the responsible law agency parties to testify as witnesses at an evidentiary hearing on November 3. Now the city wants to use a November 1 status hearing to quash the subpoenas.

What’s the big deal? The city asserts the confidential identity of its undercovers is a stake. That is of course the least of it.

The city’s own evidence against the defendants, accused of marching in the street on March 26, 2017, documents police officers deciding to issue tickets. What’s clear from the video is that the police issued tickets, not to cite wrongdoers, nor to halt law-breaking, but to 1) “identify everyone”, 2) arrest an undercover agent, and 3) disperse a lawful assembly. It’s all on tape.

When defendants first grasped what they were seeing on the bodycam video, they brought it to the attention of the various municipal court judges who take turns directing the daily court matters. Asked to produce the written reports generated by the officers on the video but missing from the discovery evidence, the judges declined. Asked to subpoena the officers involved, the judges declined. After each defendant’s pro se arguments were rebuffed, one motions hearing after the other, the defendants sought legal help. Actually Judge Hayden Kane II did eventually grant a hearing to look into the video, but he told us he’d already watched it in private and was not inclined to find it relevant, so defendants were not encouraged that his opinion would change.

In the meantime civil rights lawyers were highly interested in the police activity documented by the video. They submitted 20 pages of argument for the dismissal of charges against the defendants, citing outrageous police misconduct in violation of the Code of Federal Regulations, part 23. They requested that the sheriff, the police chief, the commander of CSPD intelligence, and others named and unnamed, be subpoenaed to testify at an evidentiary hearing on October 17. That didn’t happen, as everyone saw. The subpoenas didn’t even go out.

The October 17 hearing misfire was simply the latest of months of attempts by the defendants to bring this story to light.

This time around the city wasn’t given the chance to sit on the subpoenas, they’ve been served directly. On November 1, will Judge Hoffecker invalidate the subpoenas two days before the witnesses are compelled to appear? The question reporters can ask is should she?

The city’s argument will be that the police undercover operation, however illegal, does not have anything to do with the guilt or innocence of the socialists charged with marching in the street. Outrageous police misconduct is a matter for federal court, that’s true. But have a look at the video. Notice that the first marcher fingered for arrest, the only one assigned an arrest team, was the undercover “Mark Jackson.” When the police shouted their warning that all who remained in front of City Hall would be issued citations, their only unequivocable target was Jackson.

Without the motive of arresting Jackson, whether it was to provoke the crowd or to embed their infiltrator, and until the order “LT wants everyone identified”, the police weren’t going to make any arrests. What does that say about the supposed guilt of the accused?

The police had already told the socialists “you’re free to carry on with your rally so long as you don’t step back unto the street.”

What the socialists were doing on March 26 was the essence of protected speech. But senior officers not on the scene had a crime of their own up their sleeves, and they needed an arrest or two to set it into motion.

Should we get to the bottom of this story, or let the city pretend it didn’t happen until the defendants get to turn the tables in federal court?

One presumes that undercover agents are only performing the intelligence function of surveillance, monitoring protest activity for hints of criminal behavior. At worse, we call them agent provocateurs, trying to encourage illegality, and believe that everyday nonviolent activists should know better than to be entrapped into illegal acts.

But undercover officers are much more disruptive than that. Undercovers sow dischord and mistrust among strangers who’ve come together to advocate for a common cause. Infiltrators pit activists against each other and confound organizers with sabotage. They volunteer for responsibilities then drop the ball. They complicate discussions with irrelevant, impractical, or illegal suggestions. When their ideas are rejected they express frustration by demeaning their fellow participants for being unmotivated. When “Mark Jackson” was found out, and it took many weeks for everyone to become convinced he was an undercover, he berated everyone for every personal failing in the book. He accused individuals of paranoia, ineptitude, or lacking courage. “Get back to me when you decide you want to DO SOMETHING” were his parting words.

Police infiltration harms every citizen effort to organize. The Code of Federal Regulations mandates that police agencies have suspicion of real crime before embedding infiltrators.

If CSPD or the El Paso County Sheriff’s Office or the Department of Homeland Security or the Colorado Bureau of Investigation has proof of a crime brewing among the Colorado Springs Socialists, wouldn’t we all benefit to know about it? We would if their motive is truly crime prevention.

The real identities of “Mark Jackson” and his partner “Aimee Walter” doesn’t matter at all. Who they work for is paramount. Are they “with the Sheriffs” or contracted or embedded from another agency? As the video shows, Jackson’s jittery hyperactive behavior while detained in the cruiser doesn’t give one much confidence about who law enforcement is entrusting with a loaded weapon in a crowd they hope to be inciting to riot.

The city’s determination to quash the question of whether or not such evidence exists points to police malfeasance, not the Socialists’.

Justice delayed is justice denied. Colorado Springs police infiltration operations against social justice activism should be brought to heel sooner rather than later.

OCTOBER 27 UPDATE:

According to Judge Hoffecker’s order: November 1st at 2:30pm will be the city’s next chance to quash the subpoenas. If they do not succeed, the evidentiary hearing is scheduled for November 3rd at 8:15am.

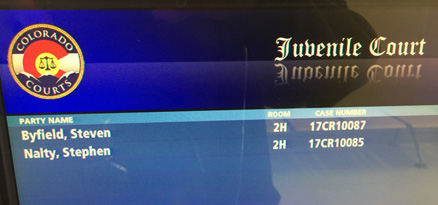

Not The People v. Stephen Nalty and Steven Byfield. Right to an Unfair Trial.

DENVER, COLORADO– The trial of accused “Paper Terrorists” Stephen Nalty and Steve Byfield began Monday in courtroom 2H of Denver district court. The two face 28 odd charges, from conspiracy, criminal enterprise, to racketeering, brought by the Colorado Attorney General and the FBI.

DENVER, COLORADO– The trial of accused “Paper Terrorists” Stephen Nalty and Steve Byfield began Monday in courtroom 2H of Denver district court. The two face 28 odd charges, from conspiracy, criminal enterprise, to racketeering, brought by the Colorado Attorney General and the FBI.

And they’re defending themselves. In handcuffs.

Don’t worry, they’re holding their own. But already it’s day one and authorities are piling on every disadvantage. On Monday the defendants were cheated of being able to prevent the state from stacking the jury (and the defendants don’t even know it because they weren’t in the courtroom to see it done).

Watching the court clerks and lawyers prepare for the trial, you cannot but admire their civil spirit. In every hearing Nalty and Byfield have declined advisements and refused to recognize the authority of their adjudicators. The two sound like broken records about “oaths” and sovereign stuff, yet the judicial mechanism inches forward. It should of course, because the defendants have been jailed since MARCH.

For six months Nalty and Byfield have been held on $350,000 bonds. Neither of them can afford even the interest on those sums. Of course their indictment and prosecution is a travesty and a misappropriation of public resources, but how else could the state stop their criminal enterprise except to admit wrongdoing itself?

Nalty and Byfield are being railroaded and they’re sure a jury will conclude the same.

The People’s Grand Jury

For the last few years, among a team of eight “sovereign citizen” types, Nalty and Byfield have been serving judges and other public officials with legal papers and liens which achieved no response. Until Colorado’s attorney general enlisted the FBI to squash the “criminal enterprise.” The sovereigns face 28 charges of all the racketeering and conspiracy lingo, essentially for questioning why their local magistrates and officials had no oaths or bonds on file. When the sovereigns got no response, they formed a “People’s Grand Jury” to indict the violators with their ad hoc public courts. Then they’d file commercial liens against those accused for defrauding the public in violation of Article 6 of the US constitution.

When confronted from podiums, judges and lawmen dismiss the oath requirement out of hand, but it’s interesting that none spell out exactly what law supersedes the US Constitution. News articles about the Paper Terrorists list the litany of criminal charges the defendants face, but have yet to mention the asserted law-breaking which is the Paper Terrorists’ only complaint.

It is hard to get a handle on what the “People’s Grand Jury” really wants. In their dreams, they assert that the lack of filing of oaths should mean that all affected legal judgements should be overturned, and that all salaries drawn by government employees who did not file oaths or bonds should be returned to taxpayers, with interest. They calculate the total sum owed to the American people is in the multi trillions. So there’s that.

Some of the public officials targeted by the People’s Grand Jury began to suffer strikes against their credit records when they didn’t contest liens filed against them. You’d think the credit monitoring algorythms would flag multi billion dollar liens. You’d think someone could suggest a method to filter such paralegal filings.

Instead the state chose to hit back hard. Last March, the eight troublemakers were indicted for two dozen paper crimes. The state imposed bonds averaging a quarter million each. It hasn’t stopped the crew, as their wives and friends keep serving more notices and liens. So now the state intends to make them examples and imprison them for life.

Jury Selection, Only For the Prosecution

Here’s what happened Monday during jury selection, when both sides are meant to parse a jury pool to pick an impartial jury. You know, a defendant’s right to a jury of their peers?

Nalty and Byfield still don’t know what hit them. The prosecution was given the jurors’ details, the defendants learned none. They blindly accepted jurors whom the prosecutors had already carefully weeded. The defendants never knew it and the court was not “on the record” when this happened because it was before the judge entered the courtroom. But audience members saw the whole thing.

Actually, once he was presiding over the entrance of the jury pool, the judge was in a position to observe the prosecution desk already progressing well through the jury questionnaires while the defendants sat idle. Perhaps the judge didn’t know his court clerk had provided no instruction to the defendants. Ultimately whose responsibility would that be?

Monday for jury selection, the court decided it needed a jury pool of SIXTY from which to choose twelve jurors plus two alternates. To save time, the court had prospective jurors fill out 4-page questionnaires instead of having them deliver the customary recitation of their biographical details. The court assigned four digit non-sequential numbers to each candidate. Copies of these forms were made for all parties, stacked according to the seating order of the jury pool. They were put on the desks before sheriffs had brought in the defendants. The team of four prosecutors began pouring over the questionnaires and were warned by the court clerk not to get them out of order as it corresponded to how the jury pool would be admitted.

Team leader, Assistant AG Shapiro noticed that the forms bore the jurors’ signatures, which he instructed should be blacked out from the copies provided to the defendants. Two clerks set themselves to redacting the stacks for defendants Nalty and Byfield. Meanwhile the prosecution studied the forms, made their notes, and drew each other’s attention to details. This information included the applicants’ names and signatures. Trial lawyers do not discount surnames and autographs as irrelevant to evaluating a juror.

When the clerks finished their redactions there were still other courtroom delays and by the time the defendants were finally brought back from their holding cell, the prosecution had a full half hour head start studying the questionnaires, and of course twice the pairs of eyes.

The defendants were not told what the stacks were, nor that they were in any order. The defendants had barely been seated before the judge made his entrance and the jury pool was paraded into the courtroom. The defendants thus got no time to examine the questionnaires. They looked at the stacks dumbly, not knowing what they were supposed to do with them, or how, with their wrists in handcuffs. Defendant Byfield tried to shuffle through some of forms while the judge advised the jury pool. With shackles on he couldn’t manage the stack, much less keep it in order, even if he knew that would matter. Forget managing pen and paper, in addition to taking notes.

You’d hope that jurors will wonder why these “paper terrorists” are kept shackled. Who has ever asserted they pose a threat of violence to anyone?

On the other hand, if you doubt that the failure to file a public oath should earn a prosecutor the accusation of fraud, if you doubt it means they’re untrustworthy, the unfairness they eagerly exploited on the first day of trial would give you pause. They behaved every bit as corrupt and mendatious as Nalty and Byfield have been saying. How unfortunate the jury didn’t see it.

As homeless defendants face camping charges, Denver courts lie to jurors.

DENVER, COLORADO- Trial began yesterday for three homeless activists charged with violating Denver’s Unauthorized Camping Law. An ordinance enacted in 2012 partly as a coordinated response to Occupy Wall Street encampments across the country, partly to smooth the city’s gentrification plans. Though six years old, the ordinance has escaped judicial scrutiny by DPD’s careful avoidance of citing only homeless victims in no position to fight the charges in court. Deliberate civil disobedience attempts have been thwarted by the city bringing other charges in lieu of the “Urban Camping Ban” for which police threatened arrests. Thus Denver Homeless Out Loud’s coup of at last dragging this sham into the Lindsey Flanigan Courthouse has generated plenty of interest. I counted four print reporters and three municipal court judges in the audience! From a jury pool of forty, city prosecutors were able to reject the many who stated outright they could not condemn the homeless defendants for the mere act of trying to survive. At one point the jury selection process was stymied for an hour trying to fill one remaining alternate seat because each successive candidate would not “check their social values at the door.” One potential juror, a hairdresser, became alarmed that all the sympathetic candidates would be purged and so she refused to say how she felt about the homeless. She was removed and they were. As usual jurors were told it was not their place to decide against enforcing bad law. Only those who agreed were allowed to stay. And of course that’s a lie. The only way bad laws are struck down, besides an act of congress, a please reflect how that near impossibility has spawned its own idiom, is when good jurors search their conscience and stand up for defendants.

For those who might have wanted to get out of jury duty, it was an easy day. Show some humanity, provoke authentic laughter of agreement by declaring “Ain’t no way I’m convicting people for camping.” The jury pool heard that Denver’s definition of camping is “to dwell in place with ANY FORM OF SHELTER” which could be a tent, sleeping bag, blanket, even newspaper.

Several jury candidates stated they had relatives who were homeless. Another suggested it would be an injustice to press charges such as these.

“So this isn’t a case for you” the city lawyer asked.

“This isn’t a case for anyone” the prospective juror exclaimed, to a wave of enthusiam from the jury pool and audience.

Another prospect said she didn’t think this case should be prosecuted. The city attorney then asked, “so you couldn’t be fair?”

“I am being fair” she answered. All of these juror prospects were eliminated.

What remained of the jury pool were citizens who swear to uphold whatever law, however vile. One juror that remained even said she gives the benefit of the doubt to police officers. Not removed.

But there is hope because they couldn’t remove everyone. Of the six that remain, one juror agreed to follow the law, even if it was a law which he knew was wrong. That juror works in the legal cannabis industry. He admits he breaks federal law every day. That law is worng he says, but if he has to, he’ll abide by this one.

He admitted, “I can find them guilty. But I’ll have to live with that guilt for the rest of my life.” Ha. Technically the city had to live with that answer.

Another juror recognized that this case was about more than the three homeless defendants. “This case affects not just these three, but the countless homeless outside” gesturing to the whole of downtown Denver.

4/5 UPDATE:

In closing arguments the city lawyers reminded the jury that they swore to uphold the law. No they didn’t, but we’ll see what verdict emerges. After only a couple minutes from beginning deliberations, a juror emerged with this question: if the defendants are found guilty, can the juror pay their fine?

EPILOG:

Well the City of Denver breathes a sign of relief tonight. By which I mean, Denver’s injustice system, Denver’s cops, Denver’s gentrifiers and ordinary residents who are uncomfortable with sharing their streets with the city’s homeless. Today’s offenders were CONVICTED of violating the ordinance that criminalizes the poor for merely trying to shelter from the elements. Today the police and prosecutors and judge and jury acted as one to deliver a message to Denver homeless: no matter the hour, no matter how cold, pick up your things and move along.

This time it wasn’t a jury of yuppy realtors and business consultants that wiped their feet on homeless defendants. It was a cross section of a jury pool that yesterday looked promising.

Today when the jury entered with their verdict the courtroom audience was able to see which juror had been appointed the jury foreman. The revelation wasn’t comforting. Though not the typically dominating white male, this foreman was a female Air Force officer who had declared during voir dire that she had no greater loyalty than law and order. As the jury pool overflowed that first day with professions of sympathy for the homeless, it was the Air Force office, Juror Number Two, who grabbed the microphone to assert that rule of law must always prevail.

Yes, in the interest of optimism I had glossed over those lesser interesting juror statements, in hope that they were only playing to what prosecutors wanted to hear. Left on the jury was a domineering older woman who had said she gives police officers the benefit of the doubt.

An older man, an organist, whose father had been the CEO of a major Fortune 500 company, actually thought that homeless people should be arrested.

I’ll admit now that everyone’s hopes had been pinned on the pot guy who swore he’d have to live with his guilt forever. And so now it’s come to pass.

When those very small people of the jury go home tonight, and eventually read what they’ve done, upheld Denver’s odious, UN-condemned anti-homeless law, they’re going to figure out that they were made to administer the system’s final blow. And Denver couldn’t have done it without them.

The prosecutor had told the jury in her closing statement, that despite the tragic circumstances, everyone was doing their job, the police, the city attorneys, and the judge, and now the jury was expected to do its job. Except that was another lie. It wasn’t the jury’s “job”. They didn’t enlist and they weren’t paid to be executors of the city’s inhuman injustice machine. Whether by ignorance, poor education, or the courtroom team’s duplicity, this jury chose to do it.

But the ignorance runs deep. Judge Lombardi, in her closing remarks to the defendants, reiterated that all the elements had been proved and that justice was served. She praised the jury’s verdict and explained that the only way they could have found otherwise was through “jury nullification”. She said those words after the jury had been dismissed, but she said them on the record, two words that lawyers and defendants are forbidden to utter. In full Judge Lombardi added “and juries are not allowed to do jury nullification.” As if we all can be misled by that lie.

Colo. US District Court judge enjoins DIA to limit restriction of free speech (grants our preliminary injunction!)

DENVER, COLORADO- If your civil liberties have ever been violated by a cop, over your objections, only to have the officer say “See you in court”, this victory is for YOU! On January 29 we were threatened with arrest for protesting the “Muslim Ban” at Denver International Airport. We argued that our conduct was protected speech and that they were violating our rights. They dismissed our complaints with, in essense: “That’s for a court to decide.” And today IT HAS! On Feb 15 we summoned the cops to federal court and this morning, Feb 22, US District Court Judge William Martinez granted our preliminary injunction, severely triming DIA’s protest permit process. In a nutshell: no restrictions on signs, size of assemblies or their location within the main terminal (so long as the airport’s function is not impeded). Permits are still required but with 24 hours advance notice, not seven days. Below is Judge Martinez’ 46-page court order in full:

Document 29 Filed 02/22/17 USDC Colorado

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADOJudge William J. Martínez

Civil Action No. 17-cv-0332-WJM-MJW

NAZLI MCDONNELL, and

ERIC VERLO,Plaintiffs,

v.

CITY AND COUNTY OF DENVER,?

DENVER POLICE COMMANDER ANTONIO LOPEZ,

in his individual and official capacity, and?

DENVER POLICE SERGEANT VIRGINIA QUIÑONES,

in her individual and official capacity,Defendants.

________________________________________________________

ORDER GRANTING PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION IN PART

________________________________________________________Plaintiffs Nazli McDonnell (“McDonnell”) and Eric Verlo (“Verlo”) (together, “Plaintiffs”) sue the City and County of Denver (“Denver”), Denver Police Commander Antonio Lopez (“Lopez”) and Denver Police Sergeant Virginia Quiñones (“Quiñones”) (collectively, “Defendants”) for allegedly violating Plaintiffs’ First and Fourteenth Amendment rights when they prevented Plaintiffs from protesting without a permit in the Jeppesen Terminal at Denver International Airport (“Airport” or “Denver Airport”). (ECF No. 1.) Currently before the Court is Plaintiffs’ Motion for Preliminary Injunction, which seeks to enjoin Denver from enforcing some of its policies regarding demonstrations and protests at the Airport. (ECF No. 2.) This motion has been fully briefed (see ECF Nos. 2, 20, 21, 23) and the Court held an evidentiary hearing on February 15, 2017 (“Preliminary Injunction Hearing”).

For the reasons explained below, Plaintiffs’ Motion is granted to the following limited extent:

• Defendants must issue an expressive activity permit on twenty-four hours’ notice in circumstances where an applicant, in good faith, seeks a permit for the purpose of communicating topical ideas reasonably relevant to the purposes and mission of the Airport, the immediate importance of which could not have been foreseen seven days or more in advance of the commencement of the activity for which the permit is sought, or when circumstances beyond the control of the permit applicant prevented timely filing of the application; ?

• Defendants must make all reasonable efforts to accommodate the applicant’s preferred demonstration location, whether inside or outside of the Jeppesen Terminal, so long as the location is a place where the unticketed public is normally allowed to be; ?

• Defendants may not enforce Denver Airport Regulation 50.09’s prohibition against “picketing” (as that term is defined in Denver Airport Regulation 50.02-8) within the Jeppesen Terminal; and ?

• Defendants may not restrict the size of a permit applicant’s proposed signage beyond that which may be reasonably required to prevent the impeding of the normal flow of travelers and visitors in and out of Jeppesen Terminal; and specifically, Defendants may not enforce Denver Airport Regulation 50.08-12’s requirement that signs or placards be no larger than one foot by one foot. ??

Any relief Plaintiffs seek beyond the foregoing is denied at this phase of the case. In particular, the Court will not require the Airport to accommodate truly spontaneous demonstrations (although the Airport remains free to do so); the Court will not require the Airport to allow demonstrators to unilaterally determine the location within the Jeppesen Terminal that they wish to demonstrate; and the Court will not strike down the Airport’s usual seven-day notice-and-permit requirement as unconstitutional in all circumstances.

I. FINDINGS OF FACT

Based on the parties’ filings, and on the documentary and testimonial evidence received at the evidentiary hearing, the Court makes the following findings of fact for purposes of resolving Plaintiffs’ Motion.?

A. Regulation 50

Pursuant to Denver Municipal Code § 5-16(a), Denver’s manager of aviation may “adopt rules and regulations for the management, operation and control of [the] Denver Municipal Airport System, and for the use and occupancy, management, control, operation, care, repair and maintenance of all structures and facilities thereon, and all land on which [the] Denver Municipal Airport System is located and operated.” Under that authority, the manager of aviation has adopted “Rules and Regulations for the Management, Operation, Control, and Use of the Denver Municipal Airport System.” See https://www.flydenver.com/about/administration/rules_regulations (last accessed Feb. 16, 2017). Part 50 of those rules and regulations governs picketing, protesting, soliciting, and similar activities at the Airport. See https://www.flydenver.com/sites/default/files/rules/50_leafleting.pdf (last accessed Feb. 16, 2017). The Court will refer to Part 50 collectively as “Regulation 50.”

The following subdivisions of Regulation 50 are relevant to the parties’ current dispute:

• Regulation 50.03: “No person or organization shall leaflet, conduct surveys, display signs, gather signatures, solicit funds, or engage in other speech related activity at Denver International Airport for religious, charitable, or political purposes, or in connection with a labor dispute, except pursuant to, and in compliance with, a permit for such activity issued by the CEO [of the Airport] or his or her designee. . . .” ?

• Regulation 50.04-1: “Any person or organization desiring to leaflet, display signs, gather signatures, solicit funds, or engage in other speech related activity at Denver International Airport for religious, charitable, or political purposes, or in connection with a labor dispute, shall complete a permit application and submit it during regular business hours, at least seven (7) days prior to the commencement of the activity for which the permit is sought and no earlier than thirty (30) days prior to commencement of the activity. The permit application shall be submitted using the form provided by the Airport. The applicant shall provide the name and address of the person in charge of the activity, the names of the persons engaged in the activity, the nature of the activity, each location at which the activity is proposed to be conducted, the purpose of the activity, the hours during which the activity is proposed to be conducted, and the beginning and end dates of such activity. A labor organization shall also identify the employer who is the target of the proposed activity.”

• Regulation 50.04-3: “Upon presentation of a complete permit application ?and all required documentation, the CEO shall issue a permit to the applicant, if there is space available in the Terminal, applying only the limitations and regulations set forth in this Rule and Regulation . . . . Permits shall be issued on a first come-first served basis. No permits shall be issued by the CEO for a period of time in excess of thirty-one (31) days.” ?

• Regulation 50.04-5: “In issuing permits or allocating space, the CEO shall not exercise any discretion or judgment regarding the purpose or content of the proposed activity, except as provided in these Rules and Regulations. The issuance of a permit is a strictly ministerial function and does not constitute an endorsement by the City and County of Denver of any organization, cause, religion, political issue, or other matter.” ?

• Regulation 50.04-6: “The CEO may move expressive activity from one location to another and/or disperse such activity around the airport upon reasonable notice to each affected person when in the judgment of the CEO such action is necessary for the efficient and effective operation of the transportation function of the airport.” ?

• Regulation 50.08-12: “Individuals and organizations engaged in leafleting, solicitation, picketing, or other speech related activity shall not: * * * [w]ear or carry a sign or placard larger than one foot by one foot in size . . . .” (underscoring in original).

• Regulation 50.09: “Picketing not related to a labor dispute is prohibited in ?all interior areas of the Terminal and concourses, in the Restricted Area, and on all vehicular roadways, and shall not be conducted by more than two (2) persons at any one location upon the Airport.” ?

• Regulation 50.02-8: “Picketing shall mean one or more persons marching or stationing themselves in an area in order to communicate their position on a political, charitable, or religious issue, or a labor dispute, by displaying one or more signs, posters or similar devices” (underscoring in original).

The Airport receives about forty-five permit requests a year. No witness at the Preliminary Injunction Hearing (including Airport administrators who directly or indirectly supervise the permit process) could remember an instance in which a permit had been denied.

?Although there is no formal written, prescribed procedure for requesting expedited treatment of permit requests, the Airport not infrequently processes such requests and issues permits in less than seven days. Last November, less than seven days before Election Day, the Airport received a request from “the International Machinists” 1 to stage a demonstration ahead of the election. The Airport was able to process that request in two days and thereby permit the demonstration before Election Day.

?

——————————

1 Presumably, the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers. ?

———————B. The Executive Order

On Friday, January 27, 2017, President Trump signed Executive Order 13769 (“Executive Order”). See 82 Fed. Reg. 8977. The Executive Order, among other things, established a 90-day ban on individuals from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States, a 120-day suspension of all refugee admissions, and an indefinite suspension of refugee admissions from Syria. Id. §§ 3(c), 5(a), 5(c). “The impact of the Executive Order was immediate and widespread. It was reported that thousands of visas were immediately canceled, hundreds of travelers with such visas were prevented from boarding airplanes bound for the United States or denied entry on arrival, and some travelers were detained.” Washington v. Trump, ___ F.3d. ___, ___, 2017 WL 526497, at *2 (9th Cir. Feb. 9, 2017). As is well known, demonstrators and attorneys quickly began to assemble at certain American airports, both to protest the Executive Order and potentially to offer assistance to travelers being detained upon arrival.?

C. The January 28 Protest at the Denver Airport

Shortly after 1:00 p.m. on the following day—Saturday, January 28, 2017— Airport public information officer Heath Montgomery e-mailed Defendant Lopez, the police commander responsible for Denver’s police district encompassing the Airport. Lopez was off-duty at the time. Montgomery informed Lopez that he had received media inquiries about a protest being planned for the Airport later that day, and that no Regulation 50 permit had been issued for such a protest.

Not knowing any details about the nature or potential size of the protest, and fearing the possibility of “black bloc” and so-called “anarchist activities,” Lopez coordinated with other Denver Police officials to redeploy Denver Police’s gang unit from their normal assignments to the Airport. Denver Police also took uniformed officers out of each of the various other police districts and redeployed them to the Airport. Lopez called for these reinforcements immediately in light of the Airport’s significant distance from any other police station or normal patrol area. Lopez knew that if an unsafe situation developed, he could not rely on additional officers being able to get to the Airport quickly.

Through his efforts, Lopez was eventually able to assemble a force of about fifty officers over “the footprint of the entire airport,” meaning inclusive of all officers already assigned to the Airport who remained on their normal patrol duties. Lopez himself also came out to the Airport.

In the meantime, Montgomery had somehow learned of an organization known as the Colorado Muslim Connection that was organizing protesters through Facebook. Montgomery reached out to this organization through the Airport’s own Facebook account and informed them of Regulation 50’s permit requirement. (Ex. 32.) One of the Colorado Muslim Connection’s principals, Nadeen Ibrahim, then e-mailed Montgomery “to address the permit.” (Ex. 30.) Ibrahim told Montgomery:

The group of people we have will have a peaceful assembly carrying signs saying welcome here along with a choir and lots of flowers. Our goal is to stand in solidarity with our community members that have been detained at the airports since the signing of the executive order, though they do have active, legal visas/green cards. Additionally, we would like to show our physical welcoming presence for any newly arriving Middle Eastern sisters and brothers with visas. We do not intend to block any access to [the Airport].

(Id.) Montgomery apparently did not construe this e-mail as a permit request, or at least not a properly prepared one, and stated that “Denver Police will not allow a protest at the airport tonight. We are willing to work with you like any other group but there is a formal process for that.” (Id.)

Nonetheless, protesters began to assemble in the late afternoon and early evening in the Airport’s Jeppesen Terminal, specifically in the multi-storied central area known as the “Great Hall.” The Great Hall is a very large, rectangular area that runs north and south. The lower level of the Great Hall (level 5) has an enormous amount of floor space, and is ringed with offices and some retail shops, but the floor space itself is largely taken up by security screening facilities for departing passengers. The only relatively unobstructed area on level 5 is the middle third, which is currently designed primarily as a location for “meeters-and-greeters,” i.e., individuals waiting for passengers arriving from domestic flights who come up from the underground train connecting the Jeppesen Terminal with the various concourses. There is a much smaller meeters-and-greeters waiting area at the north end of level 5, where international arrivals exit from customs screening.

The upper level of the Great Hall (level 6) has much less floor space than level 5 given that it is mostly open to level 5 below. It is ringed with retail shops and restaurants. At its north end is a pedestrian bridge to and from the “A” concourse and its separate security screening area.

Given this design, every arriving and departing passenger at the Airport (i.e., all passengers except those only connecting through Denver), and nearly every other person having business at the airport (including employees, delivery persons, meeters-and-greeters, etc.), must pass through some portion of the Great Hall. In 2016, the Airport served 58.3 million passengers, making it the sixth busiest airport in the United States and the eighteenth busiest in the world. Approximately 36,000 people also work at the airport.

The protesters who arrived on the evening of January 28 largely congregated in the middle third of the Great Hall (the domestic-arrivals meeter-and-greeter area). The protesters engaged in singing, chanting, praying, and holding up signs. At least one of them had a megaphone.

The size of the protest at its height is unclear. The witnesses at the evidentiary hearing gave varying estimates ranging from as low as 150 to as high as 1,000. Most estimates, however, centered in the range of about 200. Lopez, who believed that the protest eventually comprised about 300 individuals, did not believe that his fifty officers throughout the Airport were enough to ensure safety and security for that size of protest, even if he could pull all of his officers away from their normal duties.

Most of the details of the January 28 protest are not relevant for present purposes. Suffice it to say that Lopez eventually approached those who appeared to be the protest organizers and warned them multiple times that they could be arrested if they continued to protest without a permit. Airport administration later agreed to allow the protest to continue on “the plaza,” an area just outside the Jeppesen Terminal to its south, between the Terminal itself and the Westin Hotel. Protesters then moved to that location, and the protest dispersed later in the evening. No one was arrested and no illegal activity stemming from the protest (e.g., property damage) was reported, nor was there any report of disruption to travel operations or any impeding of the normal flow of travelers and visitors in and out of Jeppesen Terminal.

D. The January 29 Protest at the Denver Airport

Plaintiffs disagree strongly with the Executive Order and likewise wished to protest it, but, due to their schedules, were unable to participate in the January 28 protest. They decided instead to go to the Airport on the following day, Sunday, January 29. They came that afternoon and stationed themselves at a physical barrier just outside the international arrival doors at the north end of the Great Hall, level 5. They each held up a sign of roughly poster board size expressing a message of opposition to the Executive Order and solidarity with those affected by it. (See Exs. 2, 4, M.)

Plaintiffs were soon approached by Defendant Quiñones, who warned them that they could be arrested for demonstrating without a permit. Plaintiffs felt threatened, as well as disheartened that they could not freely exercise their First Amendment rights then and there. Plaintiffs felt it was important to be demonstrating both at that particular time, given the broad news coverage of the effects of the Executive Order, and at that particular place (the international arrivals area), given a desire to express solidarity with those arriving directly from international destinations—whom Plaintiffs apparently assumed would be most likely to be affected by the Executive Order in some way.

Plaintiffs left the Airport later that day without being arrested, and without incident. They have never returned to continue their protest, nor have they applied for a permit to do so.

E. Permits Since Issued

The airport has since issued permits to demonstrators opposed to the Executive Order. At least one of these permits includes permission for four people to demonstrate in the international arrivals area, where Plaintiffs demonstrated on January 29.

II. REQUESTED INJUNCTION

Plaintiffs have never proposed specific injunction language. In their Motion, they asked for “an injunction prohibiting their arrest for standing in peaceful protest within Jeppesen Terminal and invalidating Regulation 50 as violative of the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.” (ECF No. 2 at 4.) At the Preliminary Injunction Hearing, Plaintiffs’ counsel asked the Court to enjoin Defendants (1) “from arresting people for engaging in behavior that the plaintiffs or people similarly situated were engaging in,” (2) from enforcing Regulation 50.09 (which forbids non- labor demonstrators from holding up signs within the Jeppesen Terminal), and (3) from administering Regulation 50 without an “exigent circumstances exception.” Counsel also argued that requiring a permit application seven days ahead of time is unconstitutionally long in any circumstance, exigent or not.

III. LEGAL STANDARD

A. The Various Standards

In a sense, there are at least three preliminary injunction standards. The first, typically-quoted standard requires: (1) a likelihood of success on the merits, (2) a threat of irreparable harm, which (3) outweighs any harm to the non-moving party, and (4) that the injunction would not adversely affect the public interest. See, e.g., Awad v. Ziriax, 670 F.3d 1111, 1125 (10th Cir. 2012).

If, however, the injunction will (1) alter the status quo, (2) mandate action by the defendant, or (3) afford the movant all the relief that it could recover at the conclusion of a full trial on the merits, a second standard comes into play, one in which the movant must meet a heightened burden. See O Centro Espirita Beneficiente Uniao do Vegetal v. Ashcroft, 389 F.3d 973, 975 (10th Cir. 2004) (en banc). Specifically, the proposed injunction “must be more closely scrutinized to assure that the exigencies of the case support the granting of a remedy that is extraordinary even in the normal course” and “a party seeking such an injunction must make a strong showing both with regard to the likelihood of success on the merits and with regard to the balance of harms.” Id.

On the other hand, the Tenth Circuit also approves of a

modified . . . preliminary injunction test when the moving party demonstrates that the [irreparable harm], [balance of harms], and [public interest] factors tip strongly in its favor. In such situations, the moving party may meet the requirement for showing [likelihood of] success on the merits by showing that questions going to the merits are so serious, substantial, difficult, and doubtful as to make the issue ripe for litigation and deserving of more deliberate investigation.

Verlo v. Martinez, 820 F.3d 1113, 1128 n.5 (10th Cir. 2016). This standard, in other words, permits a weaker showing on likelihood of success when the party’s showing on the other factors is strong. It is not clear how this standard would apply if the second standard also applies.

In any event, “a preliminary injunction is an extraordinary remedy,” and therefore “the right to relief must be clear and unequivocal.” Greater Yellowstone Coal. v. Flowers, 321 F.3d 1250, 1256 (10th Cir. 2003).

B. Does Any Modified Standard Apply?

The status quo for preliminary injunction purposes is “the last peaceable uncontested status existing between the parties before the dispute developed.” Schrier v. Univ. of Colo., 427 F.3d 1253, 1260 (10th Cir. 2005) (internal quotation marks omitted). By asking that portions of Regulation 50 be invalidated, Plaintiffs are seeking to change the status quo. Therefore they must make a stronger-than-usual showing on likelihood of success and the balance of harms.

IV. ANALYSIS

A. Irreparable Harm as it Relates to Standing

Under the circumstances, the Court finds it appropriate to begin by discussing the irreparable harm element of the preliminary injunction test as it relates Plaintiffs’ standing to seek an injunction.

Testimony at the Preliminary Injunction Hearing revealed that certain groups wishing to protest the Executive Order have since applied for and obtained permits. Thus, Plaintiffs could get a permit to demonstrate at the airport on seven days’ advance notice—although Regulation 50.09 would still prohibit them from demonstrating by wearing or holding up signs. In addition, as discussed in more detail below (Part IV.B.3.c), Plaintiffs could potentially get a permit to hold a protest parade on public streets in the City and County of Denver with as little as 24 hours’ notice. And as far as the Court is aware, the two Plaintiffs may be able to stand on any public street corner and hold up signs without any prior notice or permit requirement. Thus, Plaintiffs’ alleged irreparable harm must be one or both of the following: (1) the prospect of not being able to demonstrate specifically at the airport on less than seven days’ notice, or (2) the inability to picket in opposition to the government action they oppose—that is, the inability to hold up “signs, posters or similar devices” while engaging in expressive activity at the airport. The Court finds that the second of these options is a fairly traditional allegation of First Amendment injury—even if they do apply for and obtain a permit, by the express terms of Regulation 50.09 Plaintiffs will not be allowed to carry or hold up signs, posters, or the like. The first option, however, requires more extensive discussion and analysis.

The rapidly developing situation that prompted Plaintiffs to go to the Airport on January 29 has since somewhat subsided. The Executive Order remains a newsworthy topic, but a nationwide injunction now prevents its enforcement, see Washington, ___ F.3d at ___, 2017 WL 526497, at *9, and—to the Court’s knowledge—none of the most urgent effects that led to airport-based protests, such as individuals being detained upon arrival, have since repeated themselves. Nonetheless, the circumstances that prompted this lawsuit reveal a number of unassailable truths about “freedom of speech . . . [and] the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” U.S. Const. amend. I.

One indisputable truth is that the location of expressive activity can have singular First Amendment significance, or as the Tenth Circuit has pithily put it: “Location, location, location. It is cherished by property owners and political demonstrators alike.” Pahls v. Thomas, 718 F.3d 1210, 1216 (10th Cir. 2013). The ability to convey a message to a particular person is crucial, and that ability often turns entirely on location.

Thus, location has specifically been at issue in a number of First Amendment decisions. See, e.g., McCullen v. Coakley, 134 S. Ct. 2518, 2535 (2014) (abortion protesters’ ability to approach abortion clinic patrons within a certain distance); Pahls, 718 F.3d at 1216–17 (protesters’ ability to be in a location where the President could see them as his motorcade drove past); Citizens for Peace in Space v. City of Colo. Springs, 477 F.3d 1212, 1218–19 (10th Cir. 2007) (peace activists’ ability to be near a hotel and conference center where a NATO conference was taking place); Tucker v. City of Fairfield, 398 F.3d 457, 460 (6th Cir. 2005) (labor protesters’ ability to demonstrate outside a car dealership); Friends of Animals, Inc. v. City of Bridgeport, 833 F. Supp. 2d 205, 207–08 (D. Conn. 2011) (animal rights protesters’ ability to protest near a circus), aff’d sub nom. Zalaski v. City of Bridgeport Police Dep’t, 475 F. App’x 805 (2d Cir. 2012).

Another paramount truth is that the timing of expressive activity can also have irreplaceable First Amendment value and significance: “simple delay may permanently vitiate the expressive content of a demonstration.” NAACP, W. Region v. City of Richmond, 743 F.2d 1346, 1356 (9th Cir. 1984); see also American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Comm. v. City of Dearborn, 418 F.3d 600, 605 (6th Cir. 2005) (“Any notice period is a substantial inhibition on speech.”); Church of Am. Knights of Ku Klux Klan v. City of Gary, 334 F.3d 676, 682 (7th Cir. 2003) (“given that . . . political demonstrations are often engendered by topical events, a very long period of advance notice with no exception for spontaneous demonstrations unreasonably limits free speech”); Douglas v. Brownell, 88 F.3d 1511, 1524 (8th Cir. 1996) (“The five-day notice requirement restricts a substantial amount of speech that does not interfere with the city’s asserted goals of protecting pedestrian and vehicle traffic, and minimizing inconvenience to the public.”).

This case provides an excellent example of this phenomena given that —whether intentionally or not— the President’s announcement of his Supreme Court nomination on January 31 (four days after signing the Executive Order) permitted the President to shift the media’s attention to a different topic of national significance. Thus, the inability of demonstrators to legally “strike while the iron’s hot” mattered greatly in this instance. Cf. City of Gary, 334 F.3d at 682 (in the context of a 45-day application period for a parade, noting that “[a] group that had wanted to hold a rally to protest the U.S. invasion of Iraq and had applied for a permit from the City of Gary on the first day of the war would have found that the war had ended before the demonstration was authorized”).

These principles are not absolute, however, nor self-applying. The Court must analyze them in the specific context of the Airport. But for present purposes, the Court notes that the Plaintiffs’ alleged harm of being unable to protest at a specific location on short notice states a cognizable First Amendment claim. In addition, by its very nature, this is the sort of claim that is “capable of repetition, yet evading review.” S. Pac. Terminal Co. v. Interstate Commerce Comm’n, 219 U.S. 498, 515 (1911). Here, “the challenged action”—enforcement of the seven-day permit requirement during an event of rapidly developing significance —“was in its duration too short to be fully litigated prior to its cessation or expiration.” Weinstein v. Bradford, 423 U.S. 147, 149 (1975). Further, “there [is] a reasonable expectation that the same complaining party would be subjected to the same action again.” Id. More specifically, the Court credits Plaintiffs’ testimony that they intend to return to the Airport for future protests, and, given continuing comments by the Trump Administration that new immigration and travel- related executive orders are forthcoming, the Court agrees with Plaintiffs that it is reasonably likely a similar situation will recur —i.e., government action rapidly creating consequences relevant specifically to the Airport.

Thus, although the prospect of being unable to demonstrate at the Airport on short notice is not, literally speaking, an “irreparable harm” (because the need for such demonstration may never arise again), it is nonetheless a sufficient harm for purposes of standing and seeking a preliminary injunction.

The Court now turns to the heart of this case—whether Plaintiffs are likely to succeed on the merits of their claims. Following that, the Court will reprise the irreparable harm analysis in the specific context of the likelihood-of-success findings.

B. Likelihood of Success on the Merits

Evaluating likelihood of success requires evaluating the substantive merit of Plaintiffs’ claim that Regulation 50, or any portion of it, violates their First Amendment rights. To answer this question, the Supreme Court prescribes the following analysis:

1. Is the expression at issue protected by the First Amendment? ?

2. If so, is the location at issue a traditional public forum, a designated public ?forum, or a nonpublic forum? ?

3. If the location is a traditional or designated public forum, is the ?government’s speech restriction narrowly tailored to meet a compelling ?state interest? ?

4. If the location is a nonpublic forum, is the government’s speech restriction ? ?reasonable in light of the purpose served by the forum, and viewpoint neutral?

See Cornelius v. NAACP Legal Def. & Educ. Fund, Inc., 473 U.S. 788, 797–806 (1985).

The Court will address these inquiries in turn.

1. Does the First Amendment Protect Plaintiffs’ Expressive Conduct?

The Court “must first decide whether [the speech at issue] is speech protected by the First Amendment, for, if it is not, we need go no further.” Id. at 797. There appears to be no contest that the sorts of activities Plaintiffs attempted to engage in at the Airport (including holding up signs) are expressive endeavors protected by the First Amendment. Accordingly, the Court deems it conceded for preliminary injunction purposes that Plaintiffs are likely to succeed on this element of the Cornelius analysis.

2. Is the Jeppesen Terminal a Public Forum (Traditional or Designated)?

The Court must next decide whether the Jeppesen Terminal is a public forum:

. . . the extent to which the Government can control access [to government property for expressive purposes] depends on the nature of the relevant forum. Because a principal purpose of traditional public fora is the free exchange of ideas, speakers can be excluded from a public forum only when the exclusion is necessary to serve a compelling state interest and the exclusion is narrowly drawn to achieve that interest. Similarly, when the Government has intentionally designated a place or means of communication as a public forum[,] speakers cannot be excluded without a compelling governmental interest. Access to a nonpublic forum, however, can be restricted as long as the restrictions are reasonable and are not an effort to suppress expression merely because public officials oppose the speaker’s view.

Id. at 800 (citations and internal quotation marks omitted; alterations incorporated).

a. Is the Jeppesen Terminal a Traditional Public Forum??

Plaintiffs claim that “[t]he Supreme Court has not definitively decided whether airport terminals . . . are public forums.” (ECF No. 2 at 7.) This is either an intentional misstatement or a difficult-to-understand misreading of the most relevant case (which Plaintiffs repeatedly cite), International Society for Krishna Consciousness, Inc. v. Lee, 505 U.S. 672, 679 (1992) (“Lee”).

The plaintiffs in Lee were disseminating religious literature and soliciting funds at the airports controlled by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (JFK, LaGuardia, and Newark). Id. at 674–75. By regulation, however, the Port Authority prohibited “continuous or repetitive” person-to-person solicitation and distribution of literature. Id. at 675–76. The Second Circuit held that the airports were not public fora and that the regulation was reasonable as to solicitation but not as to distribution. Id. at 677. The dispute then went to the Supreme Court, which granted certiorari specifically “to resolve whether airport terminals are public fora,” among other questions. Id.